The Embodied Restoration Lab

By Afaina de Jong

Artificial intelligence permeates our daily lives, from the mini computers we carry in our pockets to the algorithmic technology designing our built environment. These manmade technologies reflect us, our ideologies, our values—for better or for worse. As AI continues to embed itself in every aspect of our existence while reflecting the hegemonic power structures governing us—extractive capitalism, racism, the devaluing and erasure of traditional knowledge systems—there is a critical need for systemic change within these tools themselves, particularly as AI begins to influence the world at large. Whose values will shape the world-shapers’?

The Embodied Restoration Lab, an initiative conceived by architect and researcher Afaina de Jong, asks architects and designers to imagine a new kind of AI model: one that recognizes resource scarcity among various ecosystems, that prioritizes oral or diasporic knowledge, that considers accessibility needs, that moves away from paradigms of colonialism toward a more equitable future—and advises its users accordingly. As the founder of AFARAI, an Amsterdam-based studio rooted in feminist practices, de Jong has long considered the ways in which, she says, “what we can imagine as humans, as designers, and as architects is unmistakably tied to the technologies that we use and its inherent values and standardizations.” Architecture has its foundations in extractive ideologies and practices, she explains. If we change the algorithmic tools from which architects learn—the technology that helps them dream—then perhaps we can fundamentally change the world around us.

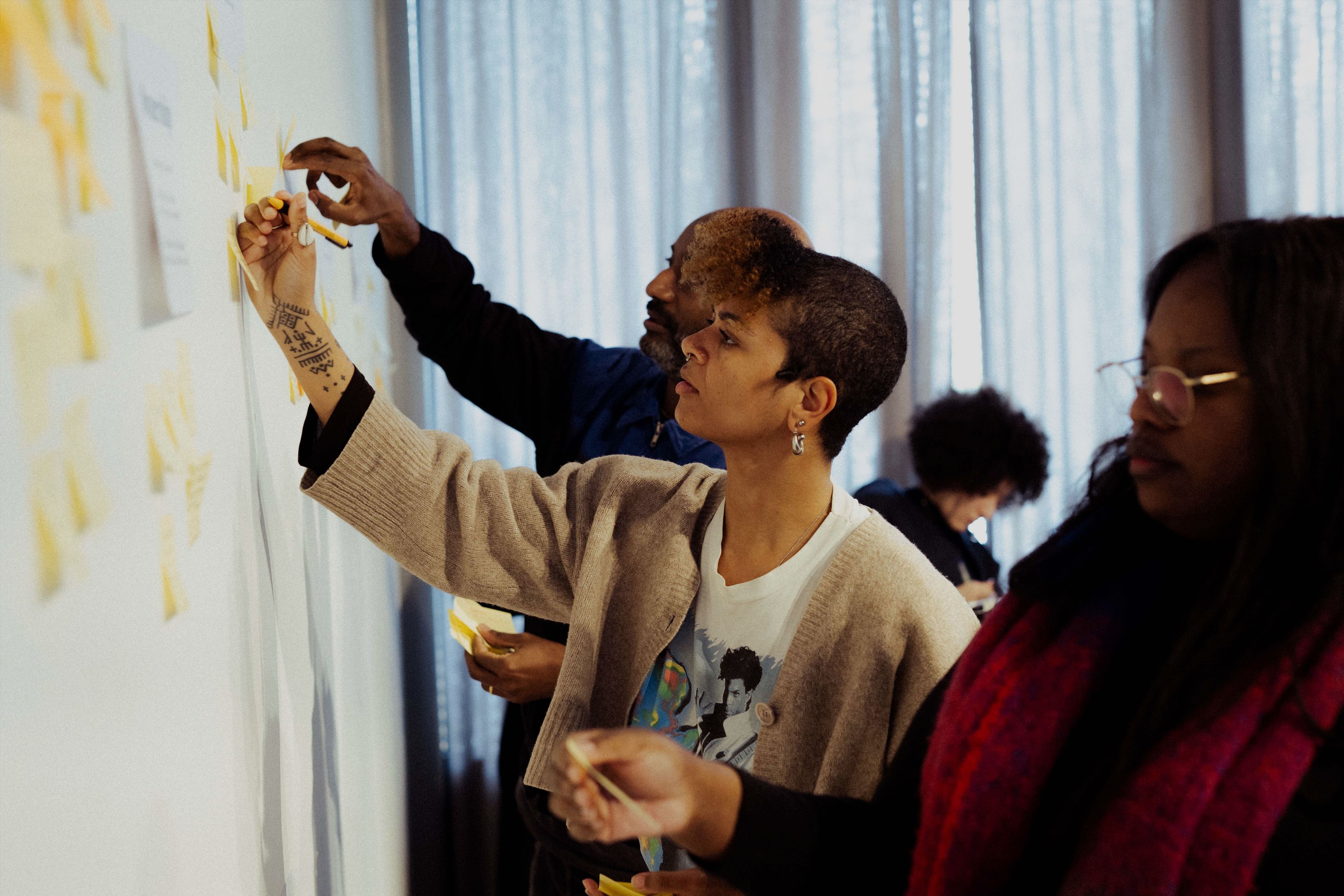

At the Embodied Restoration Lab symposium this past spring, architects, designers, and researchers gathered to teach AI new knowledge systems, and to discuss their hopes and fears for the future. Below, de Jong introduces the Embodied Restoration Lab, the questions that prompted its development, and what raising an AI—like a baby—might look like.

When did the idea for the Embodied Restoration Lab come to you? What is it like to navigate the questions the project raises, both for yourself personally and in your work with AFARAI?

From the projects I’ve developed with AFARAI in the last 18 years, a question emerged: How can we develop the architectural practice, and its complicity in social and ecological destruction, into a practice that fundamentally reimagines its own value system and way of engagement with the social and ecological? In my contribution for the Dutch Pavilion at the 17th Venice Biennale of Architecture, I identified the spatial knowledge of the overwhelming majority of othered groups—female, Black, Indigenous, of color, queer, or differently abled—as fundamental for designing for the complexity of the 21st century and for potentially arriving at an architecture of planetary well-being.

How can we develop the architectural practice, and its complicity in social and ecological destruction, into a practice that fundamentally reimagines its own value system and way of engagement with the social and ecological?

What emerged from working with both the architectural community and local communities over the years was an understanding that social and ecological disregard, extraction, and exploitation are inherent values that underlie architectural practices. This is defined, in part, by the standardization of the tools and materials that architects use. Although those tools, standards, and values are passed through generations of architects and thus shift slowly over time, contemporary architecture fundamentally continues to build upon an archive of exploitative conditions inherited through modernism and colonialism. As architects, we can engage with communities in design projects, but if we don’t change those underlying tools, we will only add incremental alterations to a flawed system.

In the age of planetary crisis, designers have to reframe how we relate to the planet and move beyond the limitations of extractive paradigms. But are we even capable of imagining new worlds, or planetary or restorative architecture, in a time of overwhelming planetary anxiety? Or are we adapting and building upon the limits of what we know already?

Can you describe generative design, including its role in the design and architectural field? And can you share a bit about how AI is currently used—or how it will be used—during the ideation step of the architectural design process?

Generative AI describes algorithms, such as ChatGPT, that can be used to create new content, including audio, code, images, text, simulations, and videos.

As the head of the MA of Contextual Design at the Design Academy in Eindhoven, I see many students wrestle with making choices out of a vast ocean of references; they’ll often relegate their design choices to collaborations with regenerative AI that’s available online, including Dall-E, Stable Diffusion, ChatGPT, Midjourney, or Dreamcatcher. What is striking is not only the contemporary entanglement of human imagination with the technological, but also that the AI-generative outcomes are never far from what already exists. This is because the inherent data and values are dictated by what has been dominant in the online human archive. How and what we can imagine as humans, as designers, and as architects is unmistakably tied to the technologies that we use and its inherent values and standardizations.

With AI entering the architectural design field, the exploration process changes. Alternatives are generated in terms of materials, manufacturing methods, cost, and more. But the entered parameters are still rooted in the standardization and values already embedded in Modernity, modern architecture, colonialism, and business-as-usual. The influence of over- and underrepresentation of data in the data sets dominates the software’s output and causes invisible bias. For example, if there is no data on the concept of a chair, or in this case architectures of planetary well-being, it is unlikely that the software will invent a new chair or a restorative architecture that can offer solutions for the 21st century.

What if the generative design algorithm calculates the cost to our ecosystem, the destruction of social equity, waste material, and human labor? What if it puts forward a different, sustainable material bank and an aesthetic imagination beyond the scope of what dominates the archives? What comes out if the generative AI has a different set of value parameters at its core? Or what if, instead of starting with a blank canvas, it starts with the embedded historic data and valued entities in the projected site? For example, for a project on Tuvalu Island—an island under threat of being submerged in the upcoming 50-100 years—imagine that the AI has an archive of architectural references from Tuvalu’s architectures and artefacts, workflows of non-extractive practices, local cultural and oral histories, and valuable real-time information on the ecological landscape in which the project will exist.

Are we even capable of imagining new worlds, or planetary or restorative architecture, in a time of overwhelming planetary anxiety? Or are we adapting and building upon the limits of what we know already?

Part of the Embodied Restoration Lab includes training an AI model to ensure it doesn’t simply reflect extractive paradigms. This will include using ethically sourced public metadata to help the AI “learn.” What are some of the values and information that should be shared with this AI? What might this training look like in practice?

One of the realizations in thinking about the AI model is that, at the moment, even current models like ChatGPT are inherently extractive. The models use enormous amounts of energy as well as data. Most of the data is used without the consent of the author, and it is unclear what relationships are made between the data and its output. There is no reference or attribution to the sources used.

So, one of the fundamental values that we explored together with Radical Data as part of the Embodied Restoration Lab was the importance of opening up and creating some transparency in the “black box” of a Large Language Model, or AI model. Participants in the lab contributed to the input in the form of texts. During our symposium for the project, people could ask the Large Language Model questions in multiple languages, and the output attributed the authors and texts that provided the basis of its answer. Another important element was addressing the energy extraction. At the moment, if you generate one image with AI, it costs roughly one bottle of water to cool the servers. Instead of running the model on the cloud, the online whole of the internet, the model could run on individual computers and as such use very little energy.

Something else that came up during the Embodied Restoration Lab symposium was the idea of understanding AI as a baby—a baby you teach, care for, and with whom you share your values. Why is a baby a helpful way of understanding this initiative?

It forces us to think of this technology as something that we can have a relationship with, something whose development we can influence. By positioning ourselves as parents, it raises questions about what kinds of values we want to pass on, and which stories and influences are important to emphasize so that we can have a positive impact on the development of a child or technology with which we will interact over a long period of time.

At the symposium, participants were also encouraged to imagine different possibilities for the future of design—and the planet itself. The conversations were vulnerable, fruitful, and required contending with one’s own anxiety about the future. This seems to be an integral part of the project: not simply training the AI, but moving through our fear to reimagine the world. Could you say more about this collective imagining?

The process to develop this regenerative design algorithm with embodied practices, and through the machine learning, will enable us to understand, teach, and learn together about how to rethink value and classification—and about how to build and organize a system as an archive in the context of restorative architecture.

I don’t see AI as something that will save us in this world filled with anxiety. Even though I am critical about AI, which can sometimes simplify complexity or engage in the same devaluation that humans do, I am also enthusiastic because the development of this proposed algorithm raises questions beyond the tool. And these questions arise through bringing people together and sharing and thinking collectively. As such, the relations that arise between people—and the relations in the thinking, experiences, and practices of different people coming together in an embodied presence—are, to me, the essence of the Embodied Restoration Lab. It’s about creating a physical embodied “system” of minds and intelligences that merge compassion, empathy, anxiety, and anger with a desire to restore some of what we imagine should be better about the world through the work we do collectively.

What if the generative design algorithm calculates the cost to our ecosystem, the destruction of social equity, waste material, and human labor? What if it puts forward a different, sustainable material bank and an aesthetic imagination beyond the scope of what dominates the archives?

Technology, and the algorithms by which it functions, reflect the worlds that built it (or, to use the baby metaphor, the worlds that raised it). By teaching these algorithms new values, can we potentially change that feedback loop, and thus our understanding of the world? I don’t think it’s lofty to imagine changing the world.

I agree. From the perspective of change, we need many different actions: it is a wide range, from direct action, to imagining the kind of world we want, to restructuring what its foundations and values should be and what they could look like. To me, imagination is fundamental, and then the work begins to realize the change. I hope that the work coming out of the Embodied Restoration Lab will help give more people, architects, and design students the tools that will embed in them a wider range of knowledge and information that is of great value to design in this century.

Participants: Radical Data, Dreaming Beyond AI, Mae-Ling Lokko, Meriem Chabani, Marga Weimans, Ramon Amaro, Camille Barton, Mario Gooden, Khensani de Klerck, Gabriela de Matos, Emanuel Admassu, Gabriel Maher, Mikaela Loach, Margarida Waco, Annika Hansteen-Izora, Marie-Louise Richards, Curry Hackett, Sarah Diedro Jordão, Afaina de Jong, Innavisions, Iyo Bisseck

Image credits: Mishael Phillip Fapohunda, Romy Zhang