Judnick Mayard on ‘Lay Me Down In Praise’

By Judnick Mayard

For much of my life I have imagined what heaven looks like. Raised in the Roman Catholic faith, I had always questioned the vagueness surrounding the urban planning of such a place. The Bible gives more a vibe of heaven than specifics and, to a child of bright imagination, it leaves much to be desired in terms of worldbuilding. How big is a place that can hold every soul from all of time for all of eternity? Is it familiar, i.e. catered to each soul’s preference, or are we made privy to something we could’ve never imagined? How would the communities and spaces that we’ve created or even destroyed in this life be repurposed in the next? The Beatitudes (a core of eight blessings believed to be delivered in a sermon directly from Jesus Christ), offer a simple all-things-will-be-switched perspective, but I wanted to be in the mind of the architect. What did he see as a perfect space for humans? I fantasised about heaven being like the Amazon, as lush and full as it looked in my National Geographic magazines. With time and age, I realised the only heaven I would be interested in is one that looks nothing like Earth as I know it, but rather as it was before us.

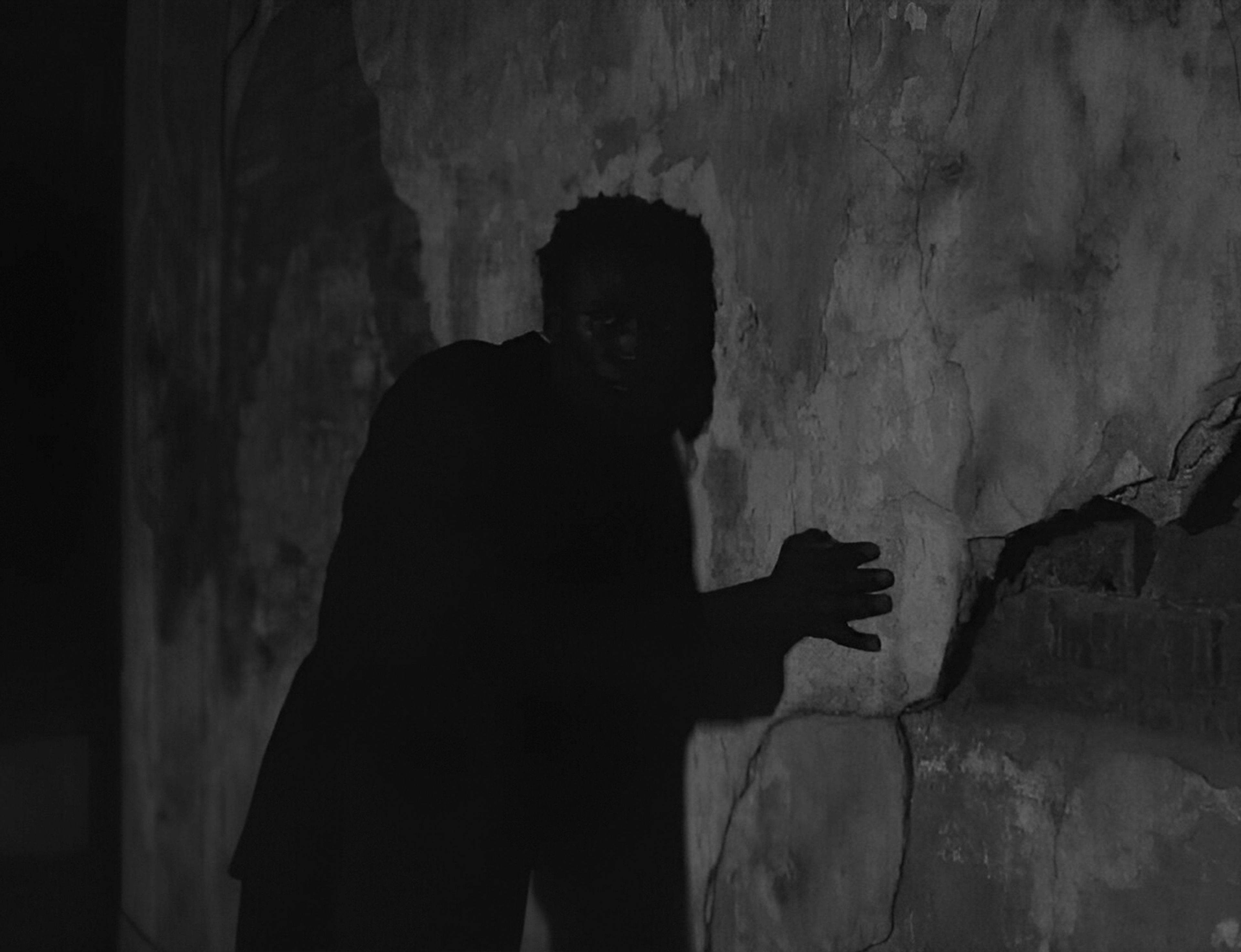

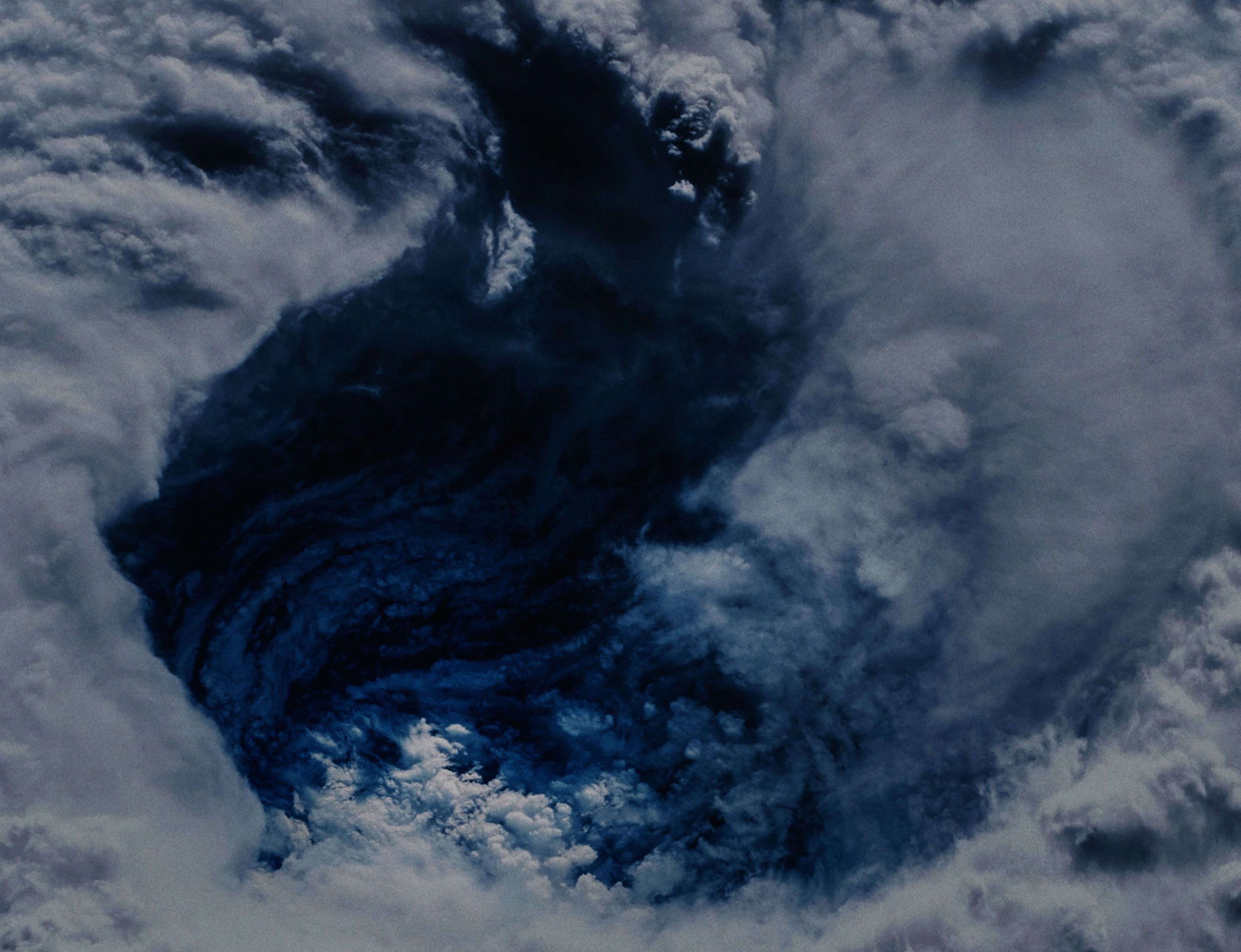

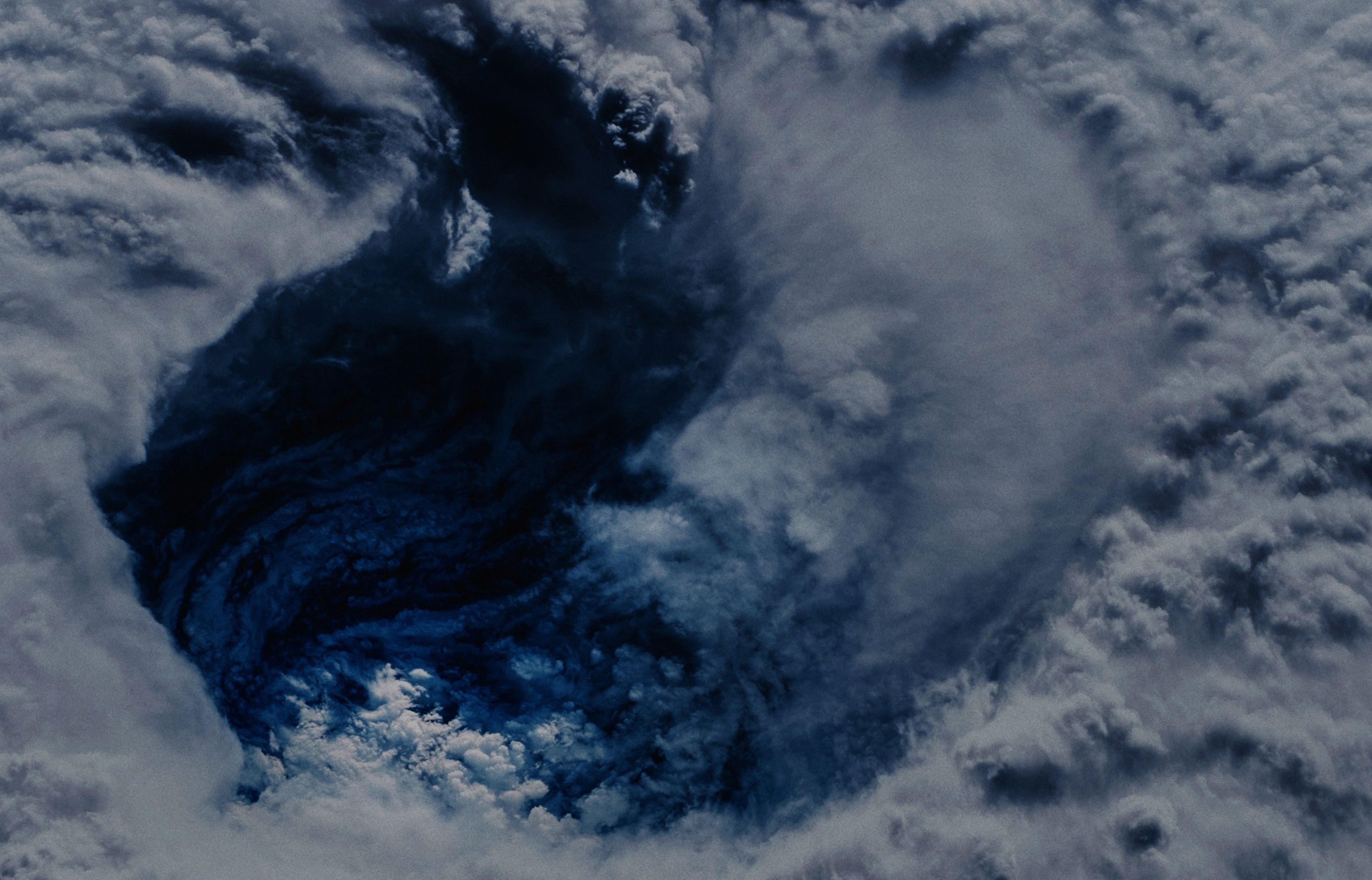

As the opening sequences of Justen LeRoy’s sensual video work, Lay Me Down in Praise washed over me, I found myself once again thinking of heaven. Something about the sound of the surf pounding against the shore attaches itself to one’s spirit. In one ear was the overbearing sound of wind, and in the other were musical notes, held in a way that reminded me of Gregorian chants—that most hollow of singing in which the notes feel more like a vacuum. The accompanying colourless images of Black people in funereal clothing juxtaposed against violent, erupting lava brought me right back to my days reading the Bible. I found myself wondering yet again: where does everyone in heaven sleep? Furthermore, I was reminded of why I had become so obsessed with the place; it was meant to be a refuge for those who could not find peace on earth. For me, a young Black girl, I wondered what a place that ended all suffering could look like and I wanted details: the weather, the landscape and, most importantly, what exactly would this paradise resemble structurally? What would its architecture be?

As a child I questioned Santa Claus’s existence because I did not have a chimney. I grew up on the second floor of a six-floor building. If not for the luck of facing a courtyard, we, like most New Yorkers, would not even have had cross-ventilation. I concluded that no gifts came for children without chimneys. Years later, I realised that I had further internalised that heaven was only for people who had a house with a backyard enclosed by forest.

Just as the images of humans are in compositional contrast with the landscape scenes on screen, we are but an interruption in the time of this planet; for those who are marginalised and oppressed, what does the eternal consist of?

Halfway through the work, LeRoy fills the three screens with images of a river running through the land, searching for the sea. The vantage points are empty of wildlife or people. What is presented is space and interspersed within it are black and white images of Black people moving their bodies to a rhythm we can’t be sure is the one we are hearing. LeRoy intends for them to occupy that space. Seen from high above, the panoramic views inspire thoughts of salvation for those who cannot find it on Earth as we know it. The bubbling lava and crushing waves are void of human design or law, and thus of human life. The human figures are always in a separate frame that keeps them suspended and protected within the sequence of locations where, in reality, their lives would not be cherished nor spared.

Schematically, the singularity of planet Earth is that, somehow, out of all the rocks in this solar system, it was the only one able to grow life: Not too close or too far from the sun, just one moon to create gravity, oxygen generated by the oceans, and space. From sea to sky to land, Earth has enough room for all its inhabitants and despite early religious beliefs, nothing ever got bumped off an edge of the globe. In its design, Earth has thought of all contingencies and needs no improvements to be inhabitable for the human species. Our sheer numbers should prove that. When we experience or look at images of nature, we feel a deep sense of approval and certainty in the structure and aesthetic of our home planet. We are compelled to remind ourselves that the environment was perfect long before us and threatens to return to its natural state after we are gone. We are not its first inhabitants, but merely the byproduct of its flawless evolutionary mechanism. Each of LeRoy’s sequences is given its own accompanying sound; a baby’s heartbeat in utero, or the breaking of waves onto shore. The human participants represent every stage of life, from old to unborn, and are presented in motion, from hugging to sitting to walking to dancing. The film is a cycle from start to finish, and one that left me wondering: would heaven not simply be Earth before civilization?

The tenor of Lay Me Down in Praise is a reverent one. The clothes are Sunday best, the concept clearly spiritual, and the title of the work itself sounds like a hymn. There is a measure of stillness within that makes twenty minutes seem like only five, though one distinctly remembers a lull of time. It evokes thoughts of the eternal. What does forever feel like and does it transcend linear time? This planet, as an object, transcends time. We speak of dinosaurs walking this same land almost a hundred million years ago, but who alive can actually process the passing of even 10,000 years? Just as the images of humans are in compositional contrast with the landscape scenes on screen, we are but an interruption in the time of this planet; for those who are marginalised and oppressed, what does the eternal consist of? Surely not slums, but also I cannot imagine heaven being a luxury condo, or any dwelling that is not open on all sides.

We mine the earth’s resources and materials for self-serving and constructed ‘needs,’ and we have depleted, marginalised, and brought down much of what remains awesome to us. It is not a wonder that the concordance of life’s essence in most of civilization lies in being one with nature.

It’s not hard to understand why I cannot, as human design has been a source of pain and destruction. A heaven that adheres to systems of class, capital, or private ownership goes against even our human understanding of “paradise." As an adult, when I think of the great plains of the sky, I still try to visualise a place with equal acreage for all. If God created heaven and Earth, and humans were made in God's image, then would Earth not already be perfect as we found it? The afterlife holds the promise of paradise for so many who cannot find space in this place. We mine the earth’s resources and materials for self-serving and constructed “needs”, and we have depleted, marginalised, and brought down much of what remains awesome to us. It is not a wonder that the concordance of life’s essence in most of civilization lies in being one with nature.

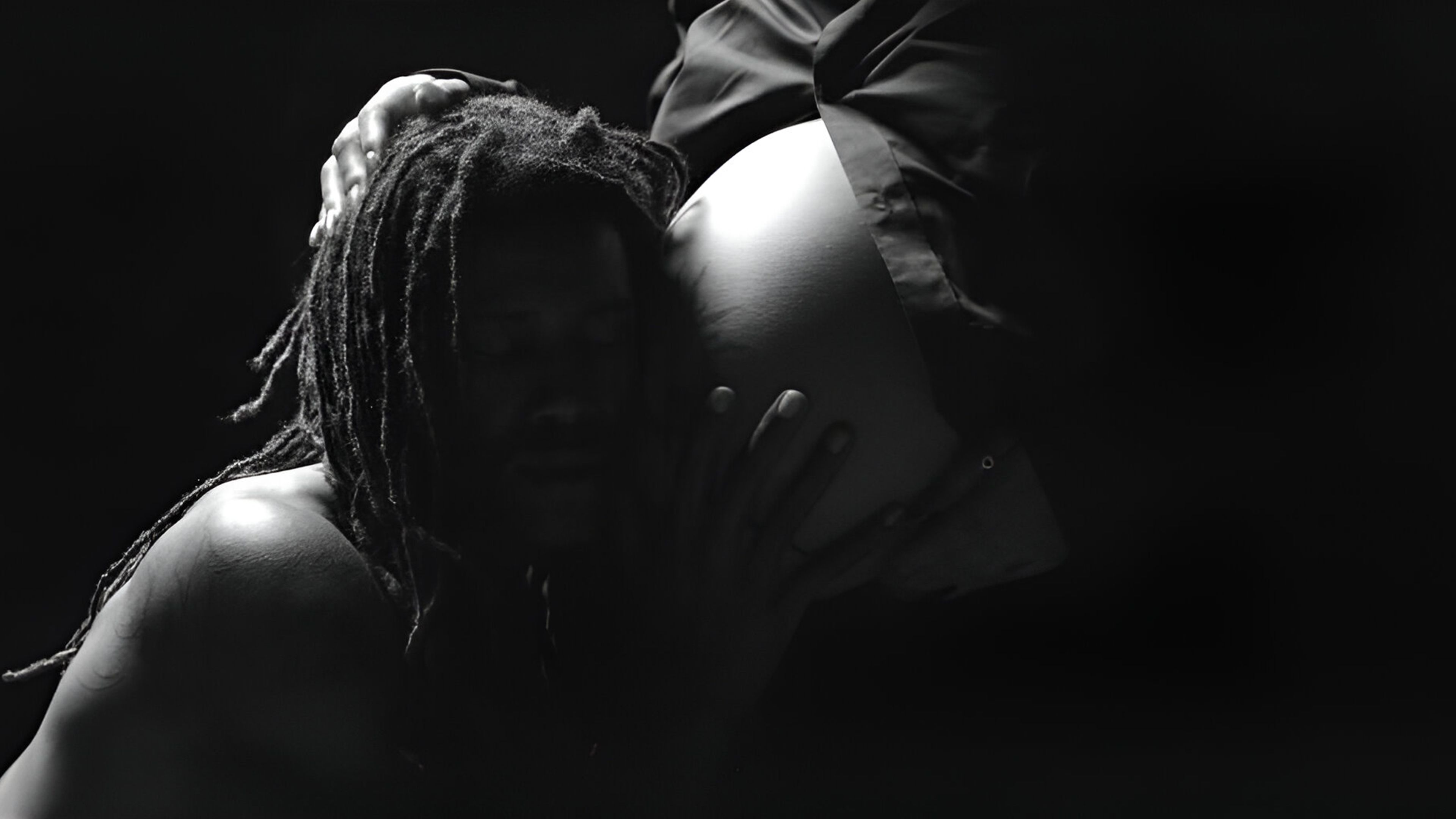

At the crescendo of Lay Me Down in Praise, Leroy presents a father kissing the womb that contains the couple’s unborn child. I wondered if the child would even get to see a world like the images surrounding them, or if these places will have already been destroyed. This is a world where an unborn Black child is already unsafe for they inhabit a Black body. The same Black bodies we must hold in mourning, in bloodshed, and in poverty. The same bodies that are only called “Black” because this word was chosen to separate and to design a world in this way. In a true heaven and in the earliest Earth, there were only people. I think of that as the film comes to an end. The heartbeat slows and the final image is of the Arctic, icebergs and shelves—filled with organisms still unknown to us—currently melting with the threat of a do-over, a restart in the evolutionary design of all life. At that moment, I could think of no better heaven than the one we’ve squandered on Earth.

Judnick Mayard is an Emmy-nominated TV writer and producer based in Los Angeles, California.

Artwork credit: Film stills from Lay Me Down in Praise (2022-23) courtesy of the artist.