Spray Foam Fumes Collapse the Distance Between Two Points

By Imani Jacqueline Brown

A few years ago, I decided that I wanted to live on a barge. Throughout the United Kingdom, a network of formerly industrial canals dredged to transport coal has over the past century become a migratory community, and the narrowboat barge form has been adapted into affordable housing. A towpath once traversed by trudging horses, edged by butterfly bush and stinging nettle, would become my front yard, shared with swans and spiders, moorhens and minnows, coots and catfish. In exchange for living more or less rent-free, I would move every two weeks, traversing twenty-one miles each year. Life on the water would be challenging, yet deeply rewarding.

As a longstanding ecological justice activist and artist raised in a region with a very different relationship to industrial canals 1, I am incredibly drawn to this world in transition, and feel akin to it. This year, with the help of a seasoned boat builder—a small family company of three with forty years of experience—I fleshed out my dream home from a shell of steel. Her name is Orion. 2

I delight in the weaving of dreams and concocting of schemes for alternative ways of being in the world. Still, I was not quite prepared for the challenges posed to my ideals by the constricted realities of building construction. It unsettles the stomach to learn how the rhetorical sausage of one’s home is made.

Between the hull and interior walls, my builder applies ‘spray foam’ insulation. He swears by the stuff, noting that in addition to keeping the space cool in the summer and warm in the winter, it would augment the stability of the frame. Even electric boat builders tout the product as an ‘energy-efficient’ and therefore sustainable solution.

With my body as its interscalar vehicle, spray foam fumes collapse the distance between Louisiana and London, between the beginning and the end of petrochemical products’ lifecycles.

Yet, I know that spray foam is no miraculous innovation. Polyurethane, or ‘spray foam’, insulation is produced from a toxic class of chemicals called isocyanates—irritants to the mucosal membranes of the eyes, as well as to the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts. They are also suspected human carcinogens known to cause cancer in non-human animals. My builder suffers from a number of serious health ailments, including heart trouble and a failing liver. I ask him why he doesn’t wear a respirator while working. It’s already too late for me, he says.

Despite my concerns and in spite of attempts to propose alternatives (fibreglass? wool?), I ultimately succumb to resignation. The spray foam goes in and is sealed off by walls of birch plywood. Once out of sight, I try to put it out of mind, but regrets and doubts about this and other choices surface and begin to spiral. Soon, the heat of summer brings the spray foam back into the open, now in the form of chemical off-gassing. It is said that smell is the closest sense to memory, and the noxious odor of isocyanates reminds me of home.

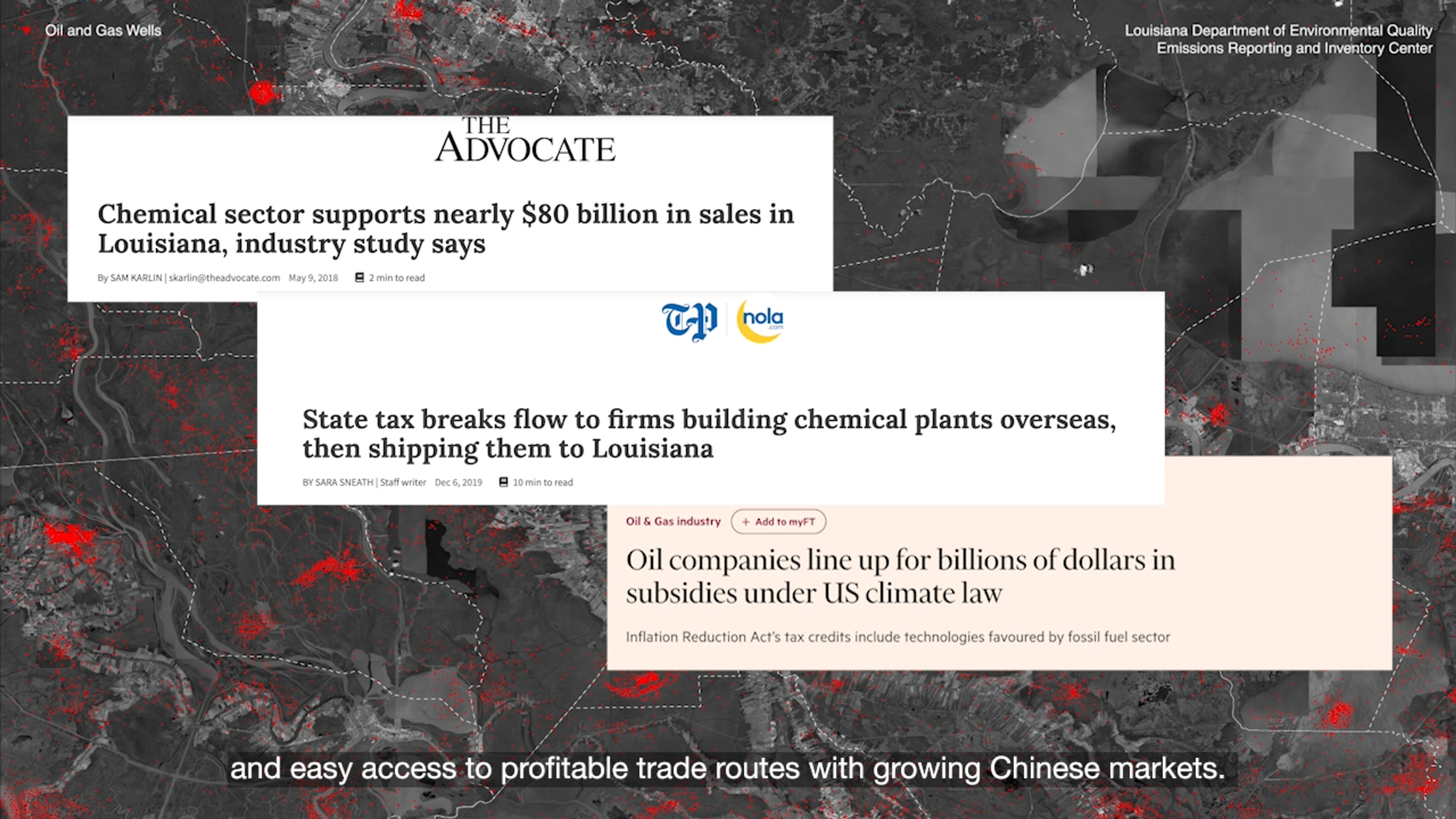

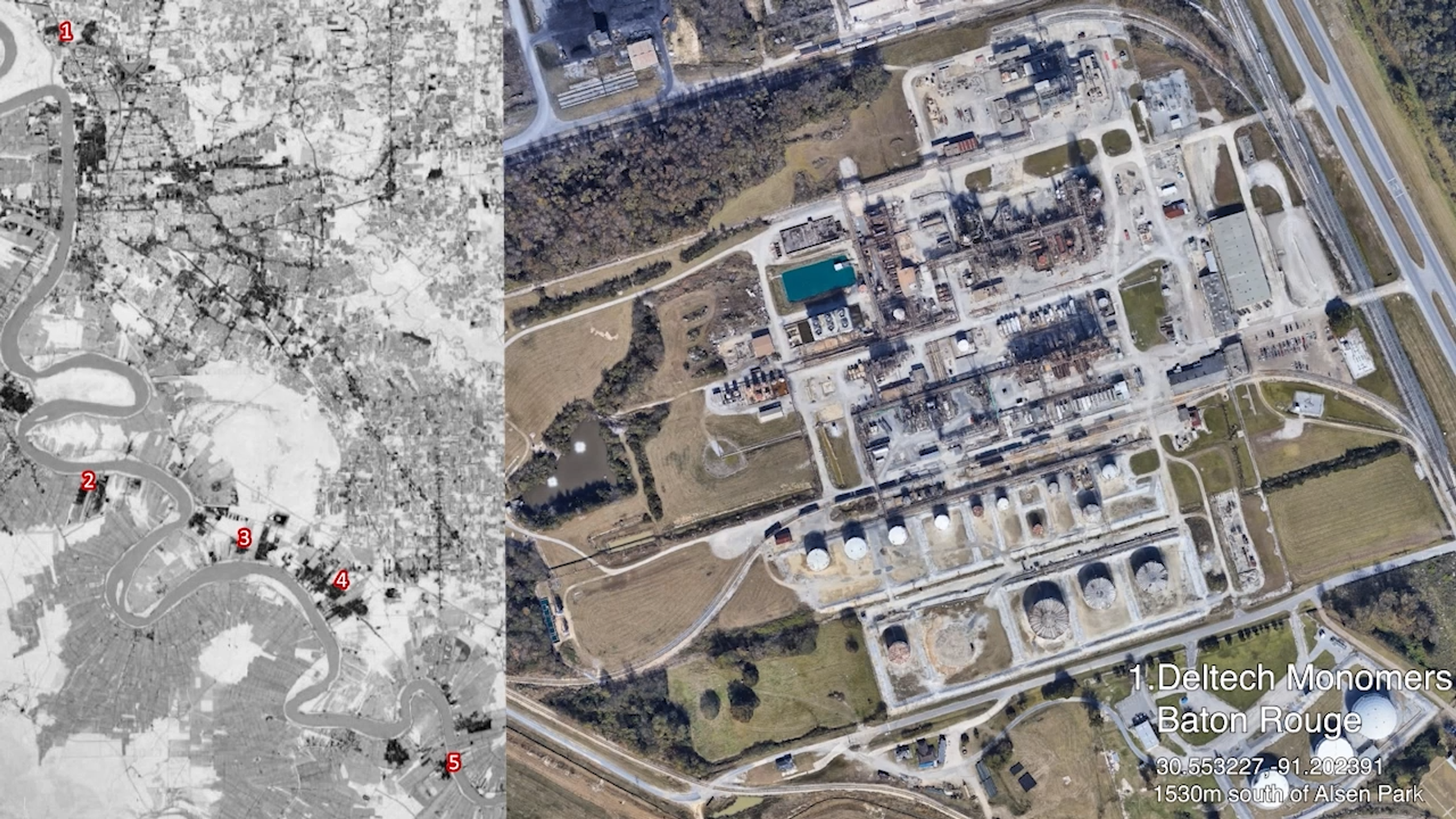

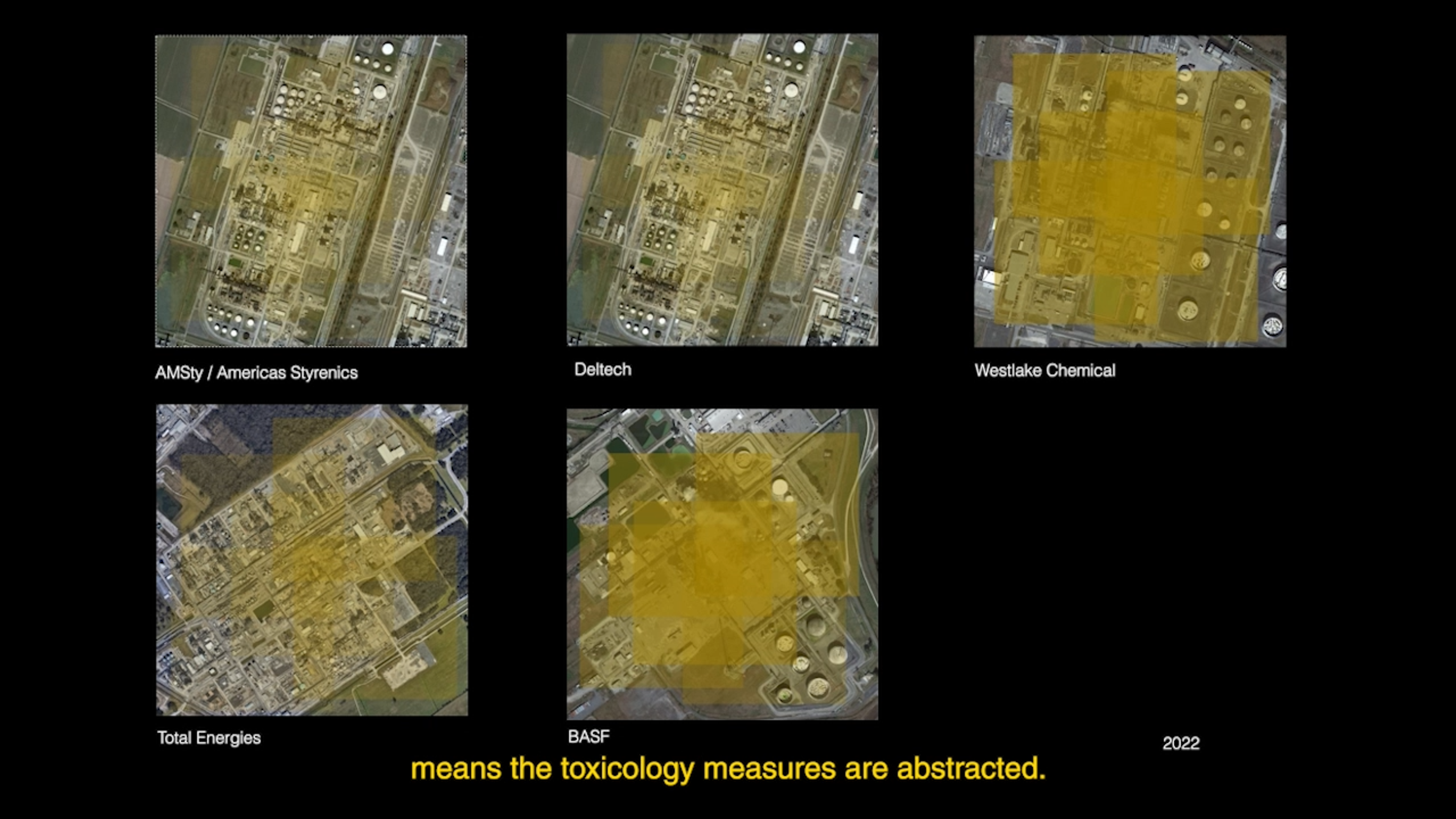

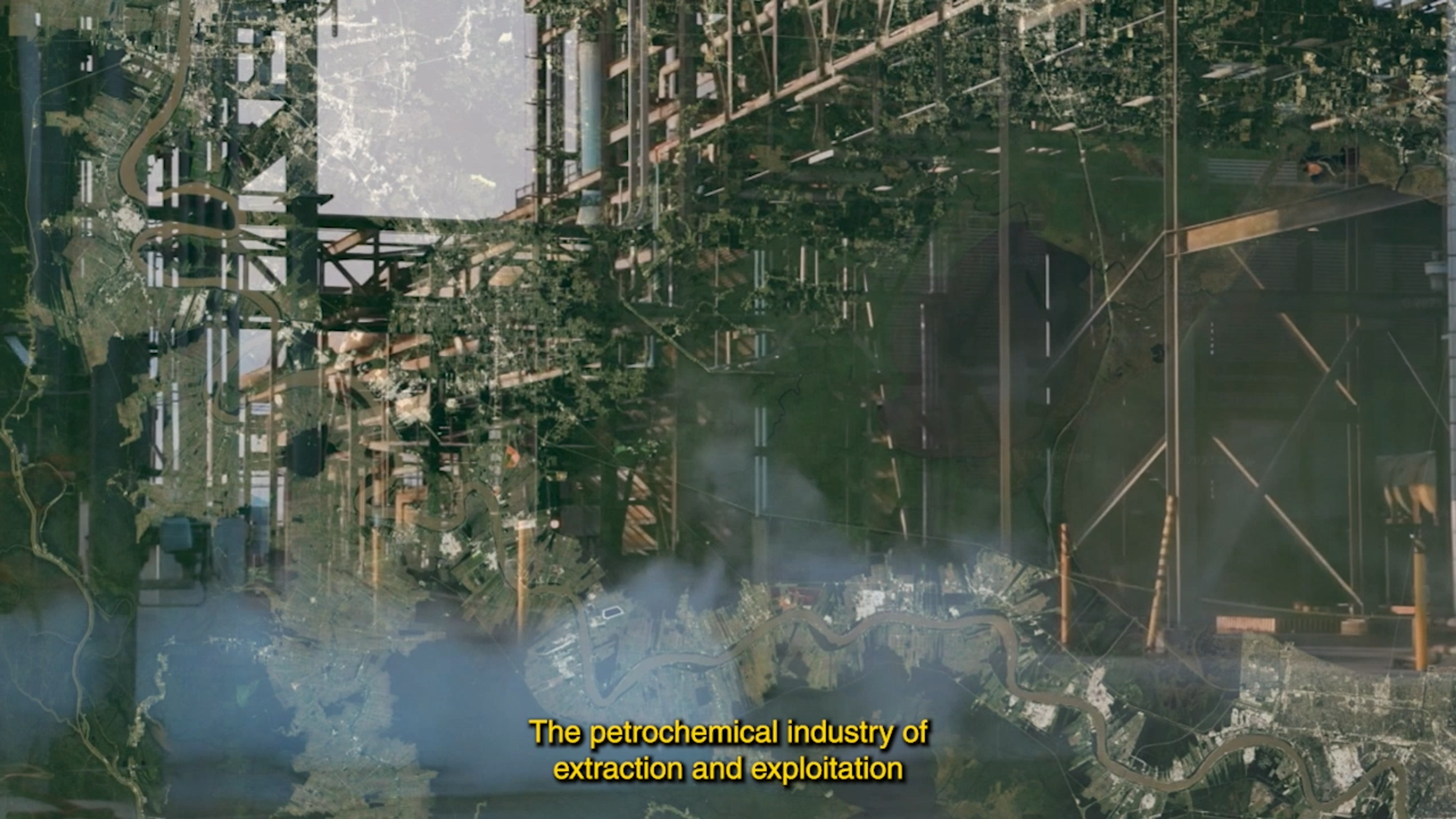

In the US state of Louisiana, along the Mississippi River between New Orleans and the state capital of Baton Rouge, stretches a region referred to by industrialists as the ‘Petrochemical Corridor,’ nicknamed by its residents as ‘Cancer Alley,’ and historically known as ‘Plantation Country.’ There, dozens of majority-Black communities are encroached upon by over two hundred (and counting) of the nation’s most polluting petrochemical plants and refineries. Each facility occupies several fallow sugarcane plantations once worked by the residents’ enslaved ancestors. Inhabitants breathe air infiltrated by emissions released during the production of the spray foam that lined my boat in London, along with scores of other petroleum-derived products and their carcinogenic chemical components. According to the EPA’s National Air Toxic Assessment (NATA), the top five census tracts with the highest cancer risks in the US are all in Louisiana.

The government’s denial of ‘offsite impacts’ brings focus to a fundamental condition of extractivism, an economic system and worldview that spans from colonialism and slavery to fossil fuel production: the invisibilization of Black and Brown bodies repositioned as ‘externalities’ and ‘collateral damage.

With my body as its interscalar vehicle 3, spray foam fumes collapse the distance between Louisiana and London, between the beginning and the end of petrochemical products’ lifecycles.

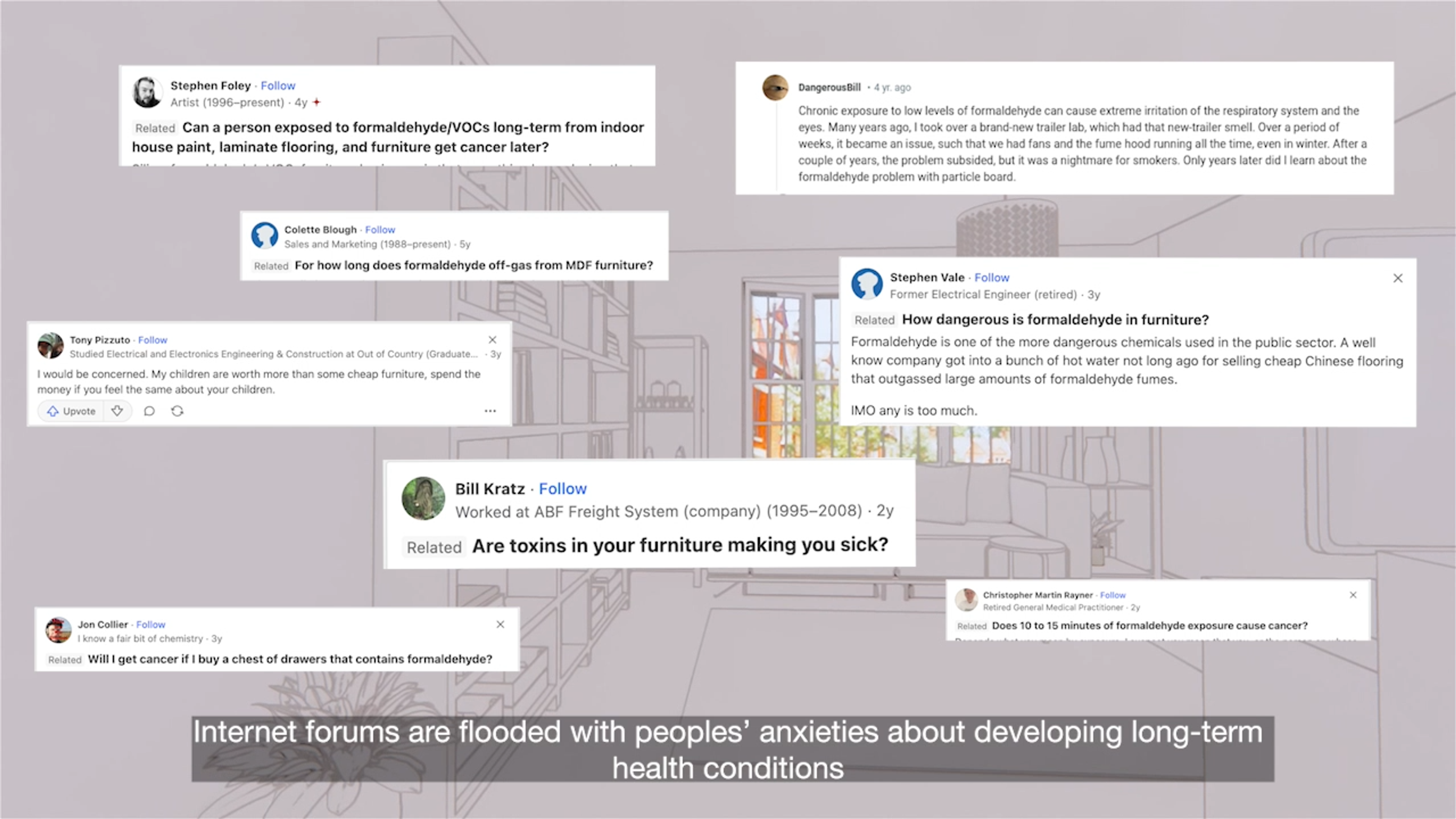

In the United Kingdom and Europe, public debates over the impact of plastics are myopically focused on the harm caused at the consumer and post-consumer end of the production cycle: macro- and mesoplastic pollution marring beaches and overflowing in rivers; micro- and nanoplastics infiltrating drinking water and fetal tissue; VOC emissions invading homes. Yet, the crisis of plastics doesn’t just begin at the end of their life cycles. Plastics radiate destruction from the moment of their creation until their non-disintegration, from point of extraction to point of emission, from nurdle to nanoplastic. (Nurdles are plastic pellets, the smallest units of plastics production. They often spill during transportation, polluting landscapes with pre-consumer microplastics.)

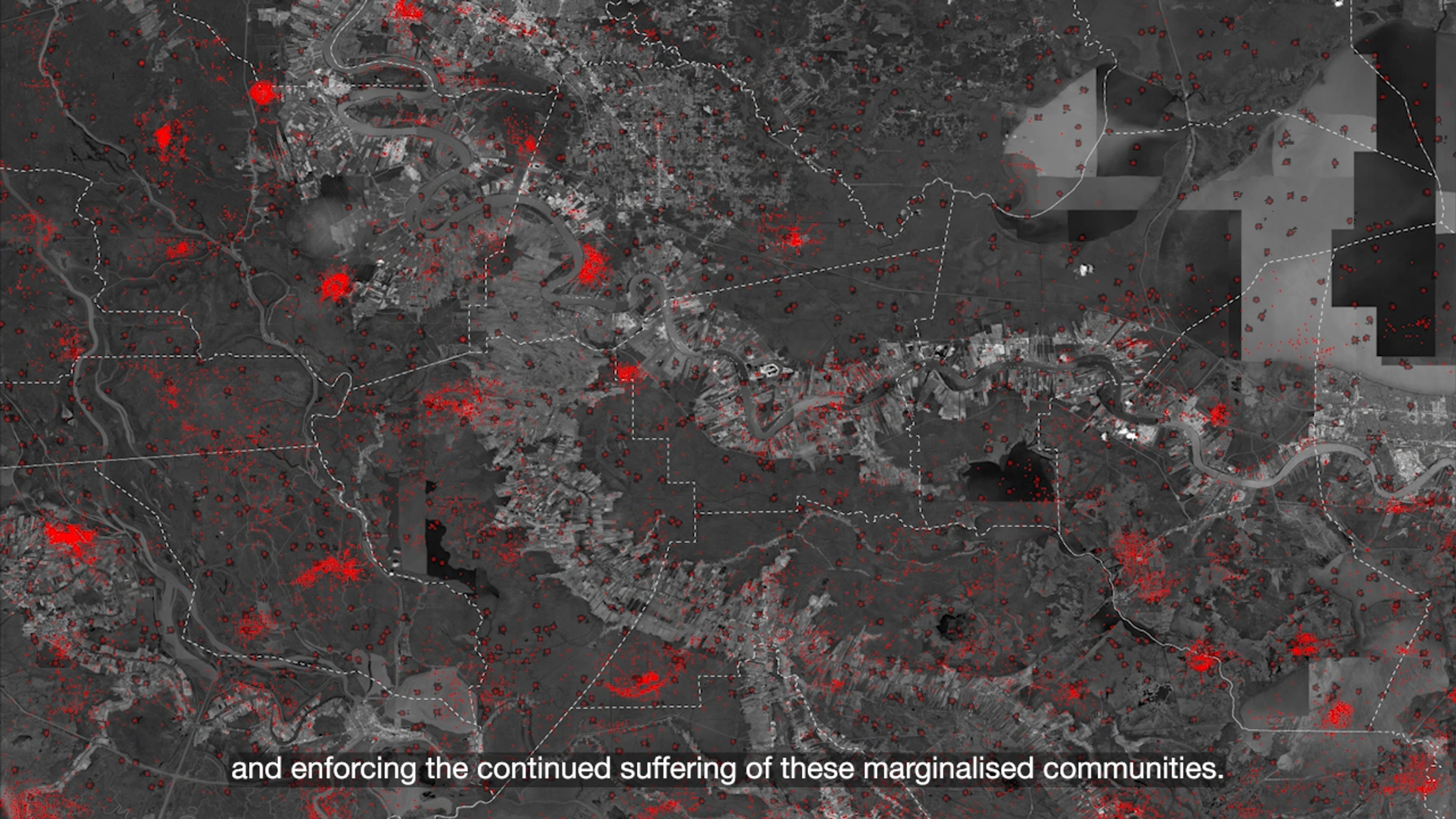

Back in Louisiana, at the origin point of spray foam’s lifecycle, 10,000 miles of canals have been dredged through the state’s once-fecund coastal wetlands to drill over 90,000 wells into subterranean fields of oil and gas. These ‘access canals’ funnel salt water from the Gulf of Mexico into freshwater wetlands, killing the vegetation that holds sediment together as land. Since the 1930s, over 2,000 square miles of land has disintegrated into the sea at one of the fastest rates of coastal erosion in the world.

The crude oil extracted from Louisiana’s wetlands is carried inland through 50,000 miles of leaking pipelines to Cancer Alley, where it is refined into its fractional parts. As the oil is heated in a distillation tower, heavier molecular compounds, such as diesel and bitumen, sink to the bottom, while lighter ones, such as gasoline and naphtha, float to the top. Naphtha, a fundamental feedstock, or building block, of synthetic plastic production, is essentially a waste product of petroleum refining. The burden of this waste product, which would otherwise need to be properly disposed of by the company, is cleverly offloaded onto us, the public and the planet, in the form of now-ubiquitous plastic commodities.

On 25 August 2023, a tank containing naphtha at Marathon Petroleum Corporation’s 576,000 barrel-per day crude oil refinery in Garyville, Louisiana, began to leak; the pool of naphtha ignited and exploded. According to records held by the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, that naphtha tank is permitted to emit benzene, a known human carcinogen. Despite the local government’s claims that there were no ‘off-site impacts,’ photographs capture a black plume towering against the sky, looming over the communities of Lions and Garyville. Satellite images reveal the plume’s path west, overshadowing the community of Wallace as it stretches across much of the state. Residents of these communities are worried; since the incident, they have complained of headaches, nausea, and dizziness.

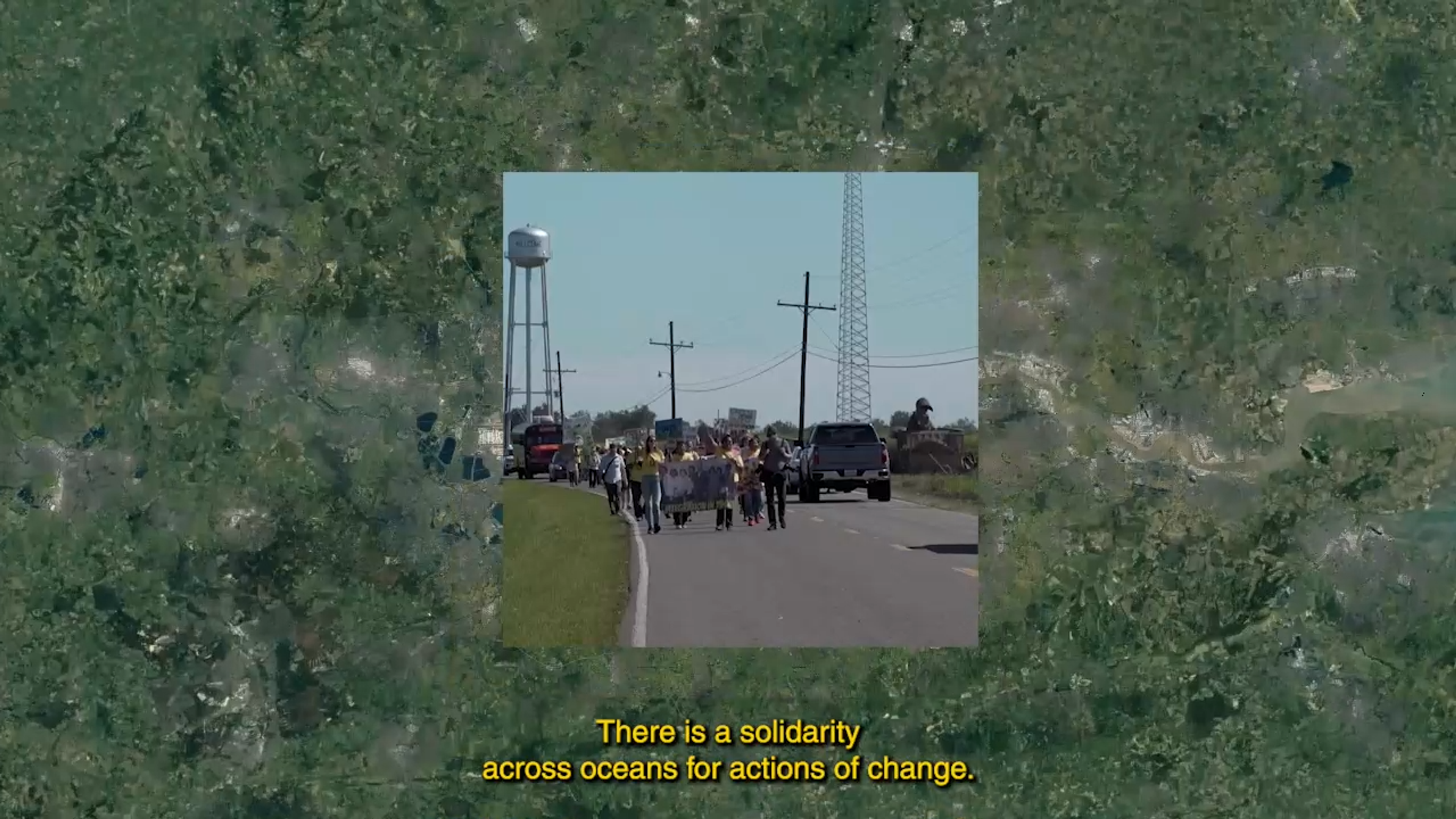

Wallace is the home of Jo and Joy Banner, co-founders of The Descendants Project. They, along with other fenceline community activist groups across Cancer Alley, including Rise St. James, Inclusive Louisiana, and the Concerned Citizens of St. John, are demanding that their government follow community leadership in implementing their sustainable economic visions for the region. If concerned publics across the Atlantic wish to stand in solidarity with their fight for environmental justice, we must support a global transition away from synthetic plastic production.

The government’s denial of ‘offsite impacts’ brings focus to a fundamental condition of extractivism, an economic system and worldview that spans from colonialism and slavery to fossil fuel production: the invisibilization of Black and Brown bodies repositioned as ‘externalities’ and ‘collateral damage’. Cancer risk, coastal erosion, plastic pollution, industrial disasters, and climate catastrophes unfurl as ‘offsite’ impacts of oil and gas production. From this perspective, we can recognise the disproportionate siting of oil and gas production facilities in majority-Black and -Brown communities as an offsite impact of the extractive colonial logics and values that codified and sanctified racial slavery, land theft, colonial rule, and Indigenous genocides across the Americas and Africa.

Recognition of this ‘continuum of extractivism’ 4 demands an urgent reconsideration of our strategic position vis-a-vis the plastics crisis. The problem with plastics is not limited to its vast carbon footprint, nor to the elongated temporality of its decomposition. The solution is not simply the elimination of single-use plastics, nor is it limited to the expansion of domestic, commercial, and industrial recycling. These earnest, honest, yet ultimately shortsighted visions of problems and solutions perpetuate the erasure of marginalised Black and Brown communities–turned–extractive zones in Louisiana and around the world. The real problem is the fallacious belief that toxic production is inevitable; the real solution is to imagine our way out of the plastics trap.

How do we do it?

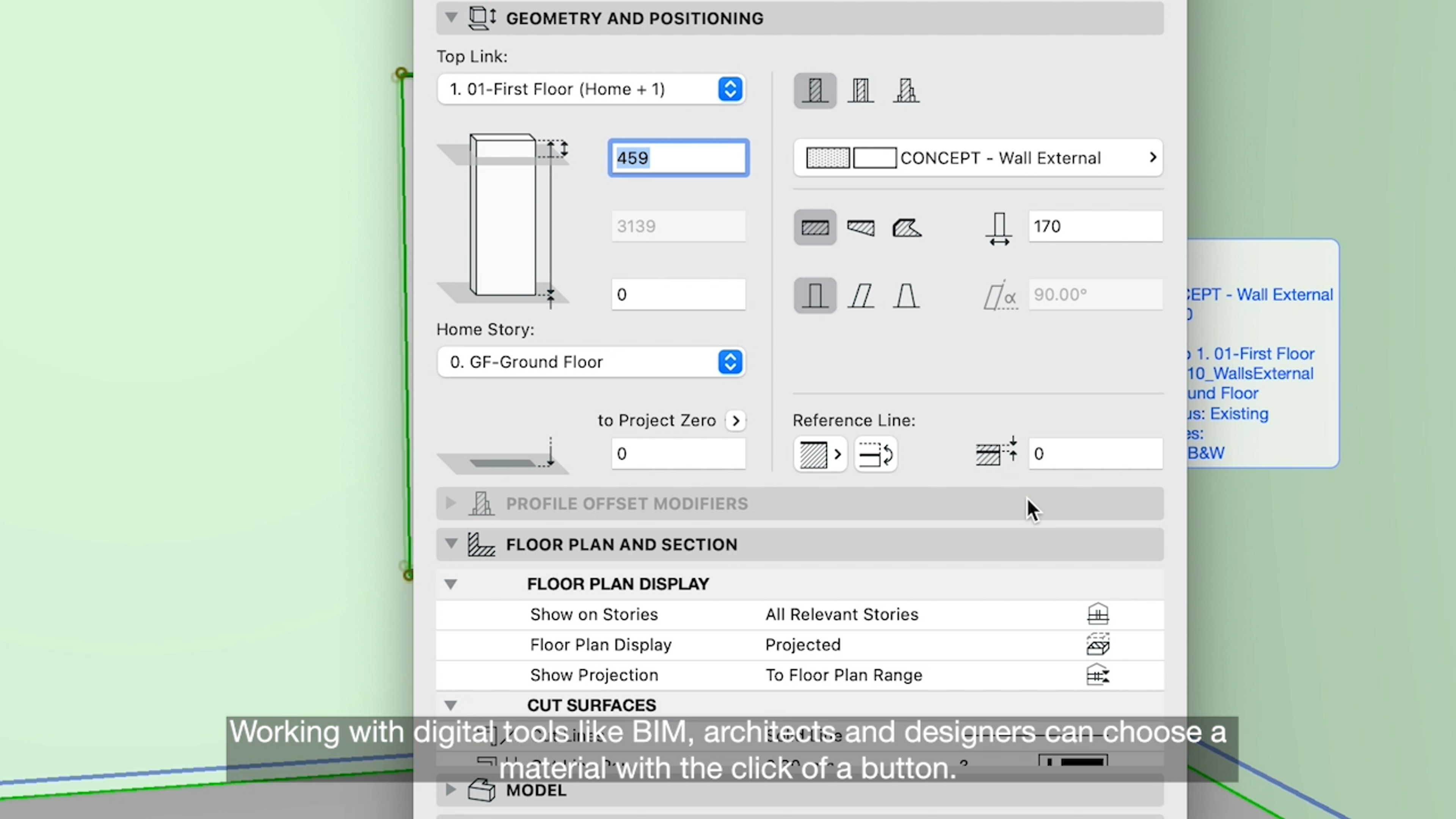

The challenge posed by spray foam came down to my own lack of knowledge of alternatives to common building construction materials. While my failure felt deeply personal, a just transition from extractivism is the journey and responsibility of not just one of us, but of all of us. I lacked not just knowledge, but an informed community of knowledge-holders and knowledge-seekers equally invested in divestment. To achieve our dreams of other worlds, we need to stimulate dialogues about best-practices, new innovations, and forgotten technologies between governments, consumers, material engineers, product designers, architects, builders, craftspeople, historians, and students. We need to respect and reconsider the vernacular practices of non-extractive, non-Western cultures around the world and throughout history. And we need to innovate ways to hold and share this knowledge. To break free from plastic is to rupture the continuum of extractivism.

So, I have asked my brilliant students to put their minds to the task. Along with my colleagues, Margarida Waco and Meriem Chabani, I run an MA Architecture studio at the Royal College of Art in London. This year, we will challenge our students to trace commonly used construction materials along the continuum of extractivism. Working with The Descendants Project and the international organisation Break Free From Plastic, our students will develop non-extractive design proposals that include plans for disseminating their material knowledge. 5

The application of spray foam in my dream home weighed me down with a sense of failure and inevitability, but I was able to channel that frustration into inspiration that carried me to a series of small victories. I located an alternative to the polyurethane lacquer recommended to treat the birch plywood walls: Osmo Oil, a wax oil made from non-synthetic materials. It produces no clouds of nanoplastic–laden sawdust during sanding and will not flake into microparticles when wet. Searching for an alternative to fossil diesel to power my boat, I researched the great leaps biodiesel has made, from ‘yo’ mama’s old fry oil’ to hydrolated vegetable oil (or HVO) which is engineered from agricultural waste oil. It is chemically indistinguishable from fossil diesel, reduces emissions by ninety percent, and is disconnected from the petrochemical production cycle.

Spray foam fumes remain an occasional uninvited guest in my home. They remind me that my own complicity with extractive and wasteful systems must be addressed in a way that is patient with and kind to myself, my health, and my process. They teach me to see my journey along the Grand Union Canal as a perfect expression of an imperfect transition, flawed yet oriented toward justice.

The UK’s canals remain heavily contaminated by their industrial past and fossil diesel–powered present. Our relationship to their feral, steampunk beauty is emblematic of the love we humans can demonstrate toward our damaged planet – toward ecologies that are far from a romantic image of pristine wilderness, that are toxified, and that still remain perfectly worthy of love, care, and regeneration, just like us.

Ashé.

Imani Jacqueline Brown is an artist, activist, writer, and architectural researcher from New Orleans and based in London. Her work investigates the “continuum of extractivism,” which spans from settler-colonial genocide and slavery to fossil fuel production and climate change. Among other things, Brown is currently a PhD candidate in Geography at Queen Mary, University of London, a research fellow with Forensic Architecture, and an associate lecturer in MA Architecture at the Royal College of Arts.