A Garden on Its Way

By Melody Stein

Territorial Empathy’s proposal for Bruckner Mott Haven Community Garden is a celebration of the community that has formed and re-formed this green space over the last half century. Landscape architect Melody Stein converses with the design collective’s founder and executive director, Zarith Pineda, about how this garden came to be, what meaningful community engagement actually looks like, and the future of Territorial Empathy’s radically inclusive approach to architectural practice.

The Bruckner Expressway begins at the Triborough Bridge, splitting into the Major Deegan Expressway to the west and Robert F. Kennedy Bridge as it exits the Bronx onto Randall’s Island. Part of Robert Moses’s totalizing plan for the Cross Bronx Expressway, the freeway and its overpasses were completed in 1973.

50 years later, on a sweltering August day, I squinted up at the steady flow of vehicles that roared atop and beneath the flying junction where expressways intersect in a perpetually tying knot of steel, dust, and sound. The unmistakable scent of tomatoes ripening in the sun filled the air. Bruckner Mott Haven Community Garden is here, an unexpected triangle of green, held on its hypotenuse by the convergence of expressways. At its gate I met Zarith Pineda, founder and executive director of the nonprofit design collective Territorial Empathy, to discuss her studio’s proposed redesign of the space slated to break ground this fall—a project they have called H.earth.

Pineda acquainted me with the 6300-square-foot site, pointing out rainwater barrels, garden beds heavy with late summer vegetables, children’s paintings left hanging on the fence after a recent community event, and a small grill resting on a stack of bricks at the very point of the triangular space. She explained her plans for the garden as we walked. “Everything is centered around the hearth,” she said, pointing down at the grill. The project title alludes to the physical cooking structure, the symbol of the hearth as representative of the home, and the planet itself.

Zarith Pineda moved from Colombia to the United States with her family when she was seven. “Being Colombian means being uniquely aware of territorial conflicts,” she says. “Our work has always come from this idea of empathy in space as a way to bring people together.” Since starting Territorial Empathy in 2018, her ideas have continued to evolve: “I’m thinking about how we can center pleasure. I think about empathy for your body. This is very much influenced by the work of adrienne maree brown,” she noted. The design of H.earth prioritises rest and sanctuary, as well as the satisfying labor of food production through gardening. “This project is not about everyone else, but it is about these people and this community. I just want them to feel good. I think feeling good should be a design question.”

This project is not about everyone else, but it is about these people and this community. I just want them to feel good. I think feeling good should be a design question.

The desire to work with communities in meaningful and truly co-creative ways was a central motivation in Pineda’s founding of the collective almost six years ago. Territorial Empathy is the only Latina-led design nonprofit in New York. The first years of operation have been far from easy: Latinx nonprofits are disproportionately underfunded, receiving less than 1% of philanthropic funding. Her experience working as a young designer in an industry that often purports to value the public realm while treating community engagement meetings as checked boxes was deeply impactful. “Offices don’t know what it takes to build trust with communities that are reasonably wary of anyone who tries to come in and change anything. This city is rapidly gentrifying and has so many issues with affordable housing. These meetings can sometimes be symbols of continued disenfranchisement,” she says. The process that led to H.earth demonstrates how Territorial Empathy works differently. “These are all these things that you really need to meaningfully understand in order to have an engagement process: childcare, translation services, MetroCards, compensating people for their time—just even making it possible for people to arrive at the table so they can give their input in a way where they feel supported, and they know what they’re giving their input about,” she said. “This is how you get great work. People are taken care of.”

This emphasis on the concrete manifestations of care extends to her organisational structure. The team behind Territorial Empathy self-identifies as a “collective,” a word Pineda substantiates through setting up projects so that each contributing designer feels ownership over the work and is fairly and transparently compensated. “I’m thinking about radical empathy with ourselves as designers because of how traumatic to the mind and body this industry can be, from the beginning of pedagogy to professional practice to licensure. I just don’t think it has to be that difficult, that painful, that exploitative,” she says, noting that the discrimination she faced early in her career has caused her to stay vigilant against replicating the same scenarios.

The history of Bruckner Mott Haven Community Garden traces that of community gardens in New York City. The garden was founded in the late 1960s, and was one of many taking root across the city. This period coincided with the political upheaval of several Central and South American countries and a resulting influx of refugees fleeing to the United States, often from agrarian communities. These immigrants soon started using the lot occupied by the present-day Bruckner Mott Haven Community Garden and the adjacent building to foster community. “This was a space for organising, resistance, and community teach-ins,” explains Pineda.

In the 1980s, the city cracked down on the activists. “It was traumatic and oppressive. The NYPD literally landed a helicopter on the rooftop and forced people out into the streets,” Pineda continues. Over the decades, the garden fell into disrepair. Without its community of stewards, the lot filled with litter, rats, and a tangle of abandoned sheds and makeshift structures. The Bronx Land Trust acquired the space in 2011, but it wasn’t until 2021 when Carolina Saavedra and the family behind a small restaurant called La Morada entered the scene and changed everything.

La Morada is a Oaxacan restaurant in Mott Haven. It’s owned and operated by the Saavedra family with the matriarch, Natalia Saavedra, working as head chef and her daughter, Carolina Saavedra, as sous chef. When COVID-19 arrived in New York City, it hit the Bronx the hardest; the borough had the highest per-case fatality in the city. The community of Mott Haven was struggling. Undocumented individuals weren’t eligible for government relief checks and a fear of deportation kept many from accessing essential services provided by city agencies and nonprofit organisations alike. The Saavedra family started cooking the food they had stored in their restaurant’s freezers and distributing it to the community. La Morada became a beacon of mutual aid and resources for a population and part of the city that continues to be systemically underserved.

Territorial Empathy’s project Design Transforms Borders featured a series of dinners and events held in Sunset Park, Brooklyn that used interactive data visualization to communicate and explore the journeys of immigrants from South and Central America to New York City.

In April 2021, Carolina Saavedra was elected by community vote to steward Bruckner Mott Haven Garden. She rallied a team of community members and volunteers to clear out the trash, construct garden boxes, institute rainwater harvest, cut back and rehabilitate historic planting, and transform the space from an abandoned lot to a lush and productive garden that serves as a community gathering space while also producing fresh vegetables for La Morada’s still-ongoing mutual aid kitchen.

Meanwhile, Pineda was also focused on understanding and responding to the needs of immigrant communities in the fallout of the pandemic and the inequities it revealed. Territorial Empathy’s project Design Transforms Borders featured a series of dinners and events held in Sunset Park, Brooklyn that used interactive data visualization to communicate and explore the journeys of immigrants from South and Central America to New York City. It was at one of these dinners that Pineda and her colleagues connected with the family behind La Morada. “Natalia was telling me that a lot of kids come to the garden and they’ve never seen where a tomato comes from. The Bronx is a food desert, particularly this area. We have Hunts Point on the other side of the Bruckner, and it’s essentially the food basket of the whole city, but people either can’t afford it or don’t have access to it. Her dream was to have a community kitchen so she could not only show them where vegetables come from, but also teach them how to cook and prepare them. I started thinking about obesity, diabetes, all the different health issues our communities face. I thought, ‘I don’t know how to do it,’ but I told Natalia, ‘I’ll figure it out.’”

When re:arc institute awarded Territorial Empathy one of its inaugural Practice Lab grants, the vision of a new garden with space for cooking, convening, gardening, and ritual practices started to feel like it had the potential to become a reality. “If we could do anything with this money and opportunity, it would be to support this labor of love that’s already been happening,” Pineda said.

H.earth uplifts and honours the practice of cooking with fire. A tall brick chimney housing a charcoal grill and carrying a shade structure and a solar-powered rainwater catchment system anchors the garden. Axial paths and planting beds fan out from this focal point. Greenhouses, composting, a picnic table, and a trio of hammocks ring the space. The formal language of H.earth is unique, reminiscent of South and Central American iconography while staying grounded in the contemporary cultures and concerns of New York City and the South Bronx. The design is a side effect of a process, a series of conversations, a method, an approach, a mindset. And it shows. H.earth is distinctive because typical formats and structures of practice do not provide pathways for translating experience into built work. “The best experts in the community are the community members,” said Pineda. “I’ve always thought about the role of the designer as a doula. Essentially, we have these tools of practice, we have this design thinking that is there to support the gestation of something that the community has manifested. We bring that into the world.” The existing garden where we sat provided the blueprint for the design that Territorial Empathy formalised and expanded upon. Days spent cultivating edible and medicinal plants, and nights spent cooking over a charcoal grill, were themselves design processes enacted by the community.

The formal language of H.earth is unique, reminiscent of South and Central American iconography while staying grounded in the contemporary cultures and concerns of New York City and the South Bronx.

While the design may be complete, the project still has a long way to go. City permitting and review processes were not set up to handle boundary-pushing and innovative design. “We’re trying to set new standards and question business as usual methods,” Pineda said, noting that one outcome of the project will be a “lessons learned” manual about how work like this could be replicated. “You get all these documents that say, ‘These are the things we do’ and it’s hard to ask, ‘Why don’t we do this really obvious solution—you must have a reason?’ Then you find that the reason is that no one tried it.”

With a limited budget and a construction schedule that hopes to deliver a completed project by the start of next spring’s growing season, Pineda is working around the clock to build political capital and find solutions. “There’s the personal responsibility of having come into this community and promising that something’s going to happen, and being worried that sometimes you don’t know how it’s going to shake out because there are only so many things you can control. It’s a lot to navigate, but it’s also really beautiful.”

H.earth is not large in scale, but Pineda is optimistic that its impact will extend far beyond the garden gate. “You really can’t dream about something that you don’t know. Hopefully this little triangle in the South Bronx inspires another community or another person to do something that someone tells them can’t be done. Maybe instead of giving up, they’ll ask, ‘Why can’t we do it?’”

Melody Stein is the founder of studio VISIT, a creative practice for land-based research, strategy, and design; a Visiting Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture at Pratt Institute; a 2023 Forefront Fellow at Urban Design Forum; and a Social Architecture member of NEW INC, the New Museum of Contemporary Art’s cultural incubator. She is also a licensed Landscape Architect in the State of Connecticut.

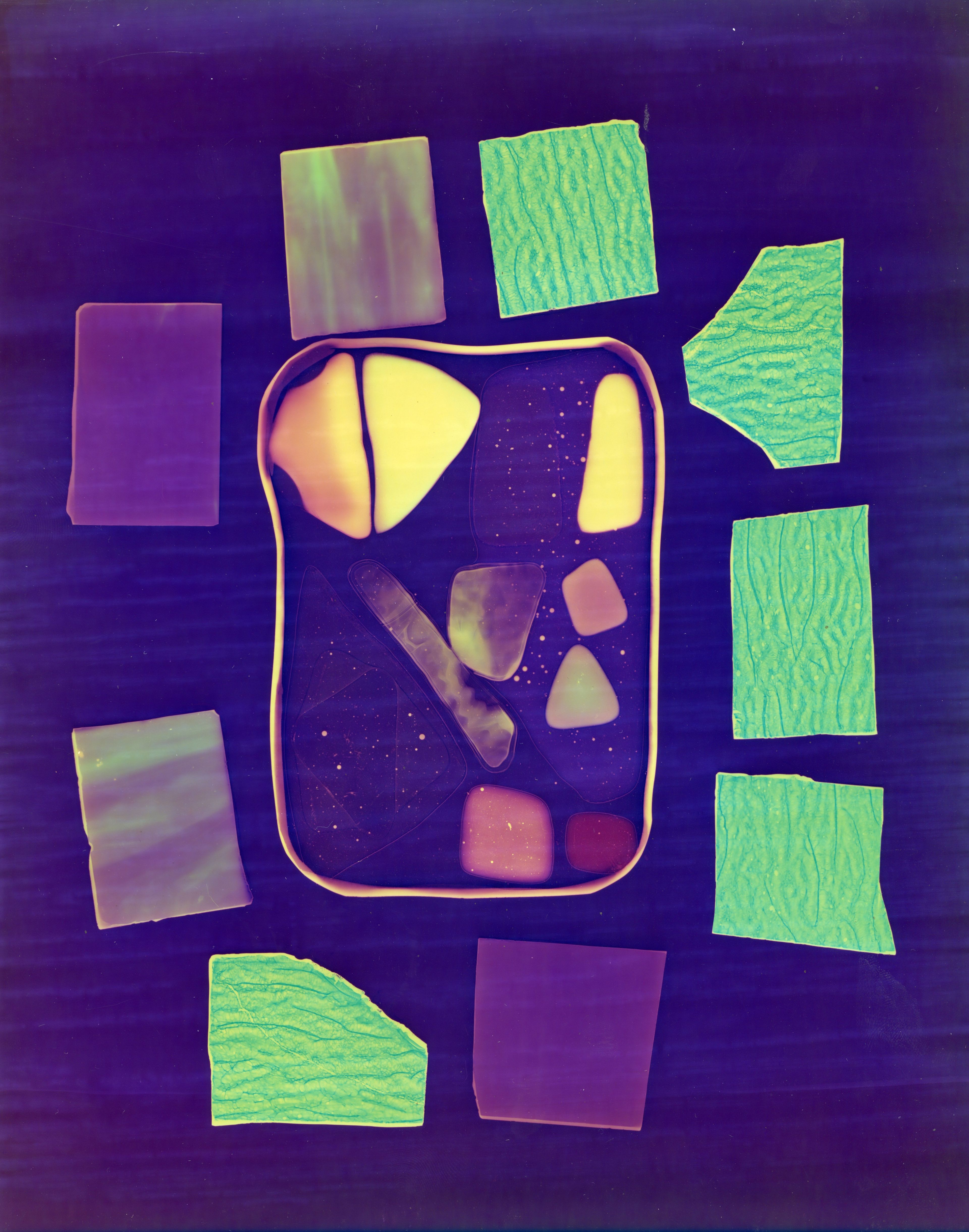

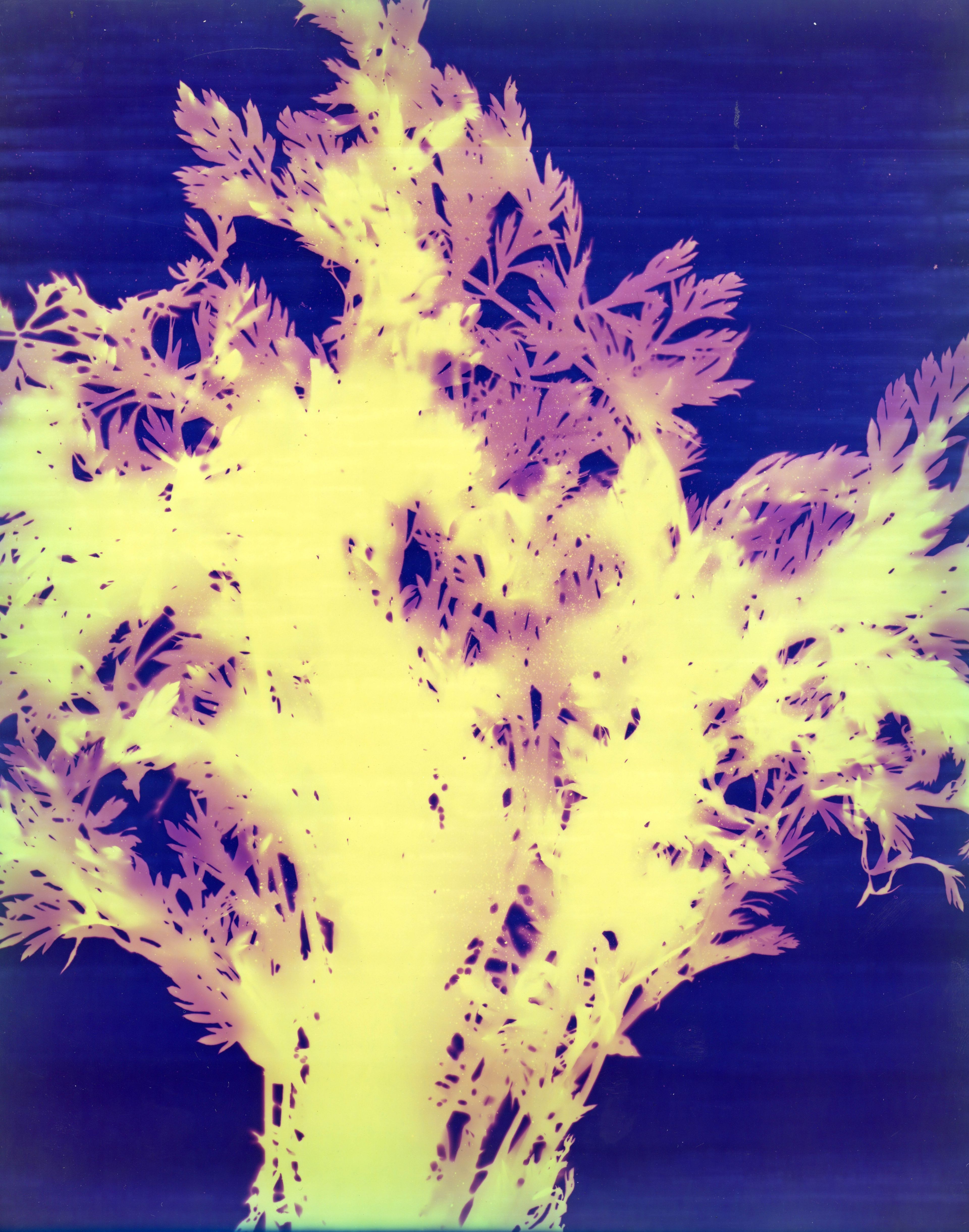

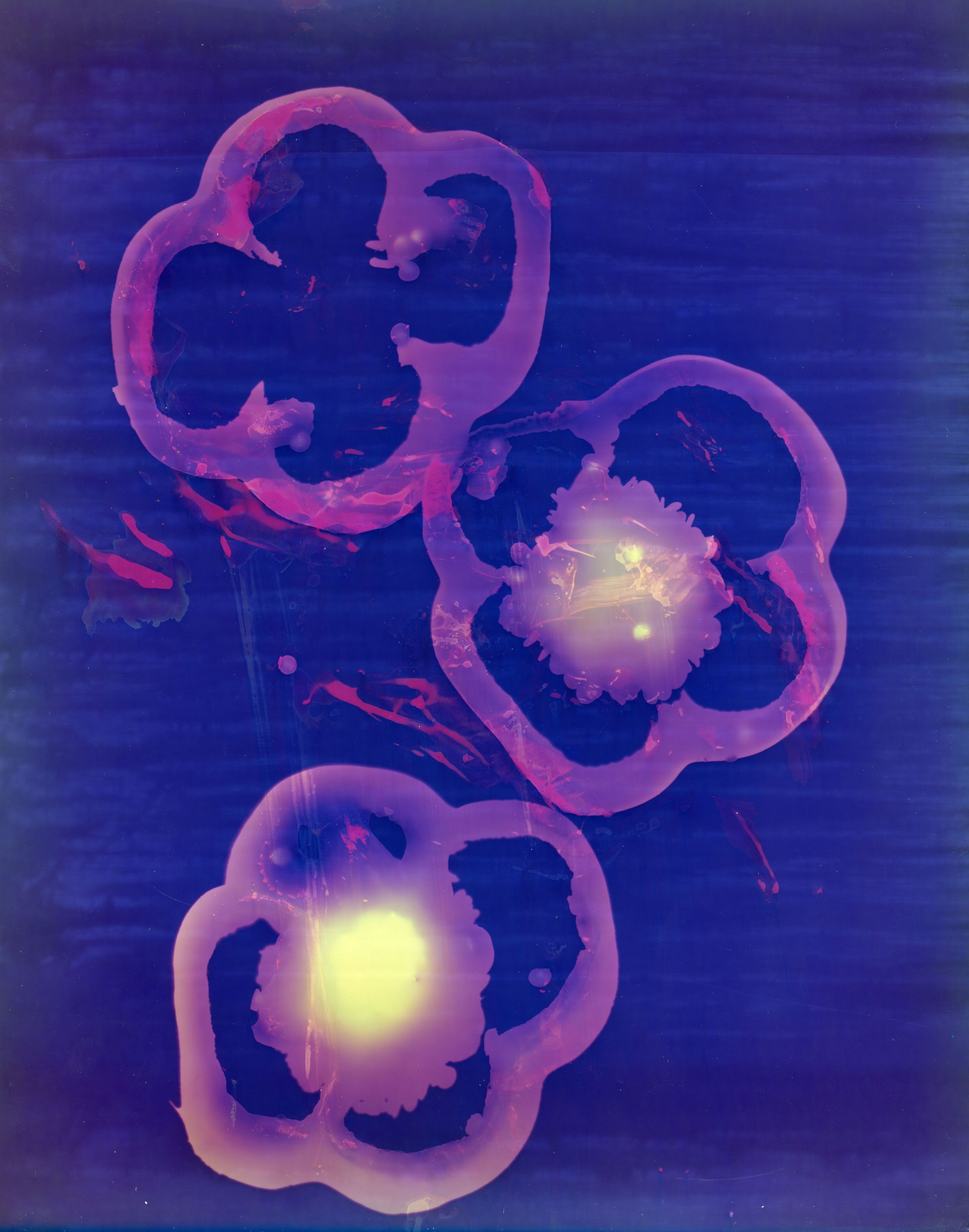

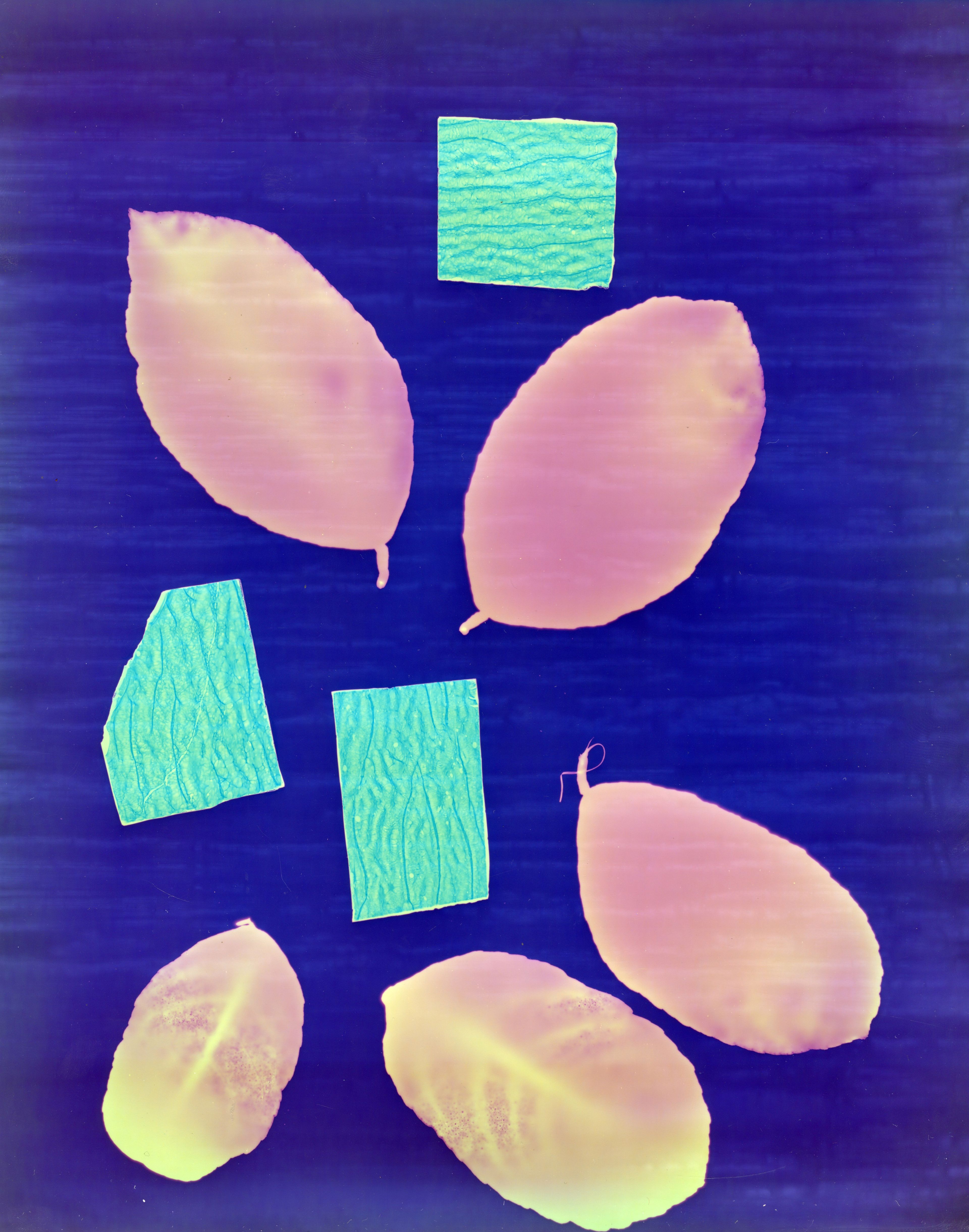

Photography Credit: Stephanie Cherry Ayala