Representing Reparations

Shumi Bose:

Hi there, and welcome to the second season of the Architectures of Planetary Well-Being podcast. The Architectures of Planetary Well-Being is a podcast exploring the interconnection of our social and ecological systems. Season two of the podcast is curated under the heading Between Us, presented by the re:arc institute and KoozArch. Between Us is a series of intimate conversations shared between two critical practitioners operating across architecture, art, curation, illustration, design, and literature. Across generational and geographical space, their discussions will move through shared aspects of practice to reach infinitely larger and more pressing issues on and around the roles of cultural practice for planetary well-being. The conversations are intended to provoke still more responses and further discussions, from micro to macro, with and led by emerging and further underrepresented communities. The guests chosen for these conversations are innovative thinkers and practitioners who we believe remain committed to the critical reframing of their disciplines and their attendant discourse.

These intimate yet wide-reaching exchanges aim to reflect the need for interdisciplinary conversation and unsiloed imagination in order to attempt the realization of a more just, caring, and restorative world.

In this episode, architect and artist Emanuel Admassu will be in conversation with researcher and architect Setareh Noorani. You'll also hear intermittently from me. I'm Shumi Bose, and I had the great pleasure of holding in conversation Emanuel and Setareh, whom I'll introduce for you now. Setareh Noorani is an architect, researcher, and curator at Nieuwe Instituut and an independent artist. Noorani's spatial and architectural designs emphasize her ongoing research into institutional spaces for collective inhabitation and appropriation, centering under-narrated voices. Setareh's current research at the Nieuwe Instituut focuses on the paradigm-shifting notions of decoloniality, feminisms, queer ecologies, non-institutional and collective representations in contemporary architecture, its heritage, and future scenarios.

Emanuel Admassu is an artist, architect, and educator. Along with Jen Wood, he's a founding partner of the art and architecture practice AD--WO. He's an assistant professor at Columbia GSAPP and a founding board member of the Black Reconstruction Collective. His design, teaching, and research practices operate at the intersection of design theory, spatial justice, and contemporary African art. The work meditates on the international constellation of Afro-diasporic spaces. Admassu's edited publication, Where is Africa: Volume 1, was published in spring 2024.

So, I'm so delighted to be talking with you both. I'm just going to imagine that we actually are either in Rotterdam or New York sitting together, and if that were the case, I'd be equally excited for you guys to meet each other. Totally thrilled to bring you together. Emanuel, I think I first came across your work through your teaching when I came to join your juries that were to do with difficult things like value and different kinds of value, embodied value and symbolic value, and all of this during 2020—that is, in the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd and, of course, during the global pandemic. Maybe we could start by, Setareh, you also have a sort of willfully ill-defined practice. You have many, many things that you do. Could you talk about that a little bit?

Setareh Noorani:

Yeah. I think I immediately would like to open up something for Emanuel as well, this question: What lineages do we inherit or what structures do we inherit? Because that's something that I think about a lot in, yeah, quite a broad practice that I try to keep myself busy with, both within the institutions I work for and Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam, which also holds a national collection for architecture and urban planning. So there, you already have the bleeding in of these types of histories, lineages, what gets carried over and what gets almost emitted to contemporary and future audiences when it comes to architecture, either capitalized or architecture culture.

My own practice, aside from that is leaning, sort of floating in between art and architecture. At least what drives me is to think about how we can open up spaces for collective free appropriation and use, right, and how we can think of them as almost the carriers or the vessels or the nodes in between various practices, embodied practices of freedom, and then, you know… To see that also as learning from how we continue certain practices that are rooted in the past and to try and dig them up to almost make your own book of examples. I don't like to use the word “canon.” I think it's outdated, but really to look at on whose shoulders we stand in such a way, I believe, that both my research practice and my design practice sort of intertwines with each other quite nicely. I learn things and then I try to practice them.

Emanuel Admassu:

Yeah. I mean, it seems like just looking at your work there's a lot in common. I'm teaching a studio right now, just trying to think about archives in general, and especially archives as they relate to looted artifacts from Asia and Africa that are currently placed in various European institutions. And as part of that exercise with my students, we read [Saidiya] Hartman's Venus in Two Acts, and it's just such an incredible text to keep going back to because at the end of the day, part of the work is not only articulating the limits of the archive, but also refusing to be included within the archive.

So I think, somehow, these acts of refusal also open up space for other forms of practice. And I think in the brief encounter I've had with your practice, it seems like we have similar orientations of not being satisfied with the limits of architecture and trying to find other vocabularies and other practices beyond architecture that allow us to engage with certain questions. In my practice, which is a partnership with Jen Wood, we kept running up against the limits of architectural representation and architectural discourse. And the most liberating moment was when we actually started to understand how specific artists are speaking about their research and also speaking about their production, and that seemed much less cumbersome than the language we use to talk about architecture. So, that engagement is not necessarily to find tools that we can bring back into architecture, but actually saying we do both, and navigating those two realms has been super generative for the practice. And also, it has opened up the types of questions we're able to ask ourselves and the type of objects and images we're able to produce.

SN:

Yeah. I'm actually really glad that we are able to engage in this conversation together because, as you say, there's a lot of overlap or at least shared values between our works. I'm just curious also, how do you think about your educational practice, almost also as a practice for freedom to go beyond these limits of discourse? How do you involve that in your education?

EA:

I think things have changed, at least I would say, from the time I was a grad student to the moment where I started teaching. Things changed where, at least the folks that I was most interested in listening to in an academic environment, were folks who were posing questions that they didn't have answers to. So at least for me, the academic practice became a way to say, "Okay. These are questions that I just have really, really struggled with, and how can we frame these questions together and discuss them together?" but also come up with methodologies on how to kind of deal with the possible pitfalls of an academic environment or these academic institutions.

So, the teaching is always trying to be a few years ahead of the practice. Sometimes it's the other way around, but at least the teaching allows us to pose questions that we're working through in the practice and the students are also working on simultaneously that… Yeah, I mean for a while I was trying to keep the two things separate, but now it's just unapologetically contaminating at one another. There are discoveries made in the practice that inform the pedagogy and vice versa.

SB:

I'm also finding that in my own work—and I'm really enjoying it, actually—the sheer honesty of being able to throw yourself unashamedly towards research and to say, "That informs my teaching, that informs my work." You talked a little bit, Emanuel, about things having changed since you're a grad student, and I was going to take that as a door to unlocking a little bit of bio because you're both so articulate about your practices and your positions. You make it sound so natural. I'd love to know a little bit about how you got here. So Setareh, are you trained as an architect?

SN:

Yeah, really picking up on how I also returned back to where I was educated, the Technical University of Delft, Faculty of Architecture—yes, trained as an architect, and then returning there sometimes, stepping into types of gatherings like symposiums or giving lectures. It's all about being also very transparent on the facts of practicing, but also very much on how I came to practice or what types of practice I mobilize as an architect, because I still call myself an architect. What I found very much is that friendship was something that shaped my practice. I had the privilege, being immersed in an amazing cohort while I was still in my master's education in Delft… Really outspoken, articulate, amazing people like Oscar Wellford, Tommy Hilsey. I really also always to name them—Katrina Kukuk— like many, many more. They enriched my thinking, because it really grew from discomfort to actually mobilizing, or being able to mobilize the space of education, the time that we got there—even though we were bombarded with work—and the relationships that we cultivated, for instance, instigate counter-exhibitions to the Portrait Gallery in the Architecture Faculty that was honestly and is still, unfortunately, mostly represented by white, cis men. You see them there in the Portrait Gallery. Those are the people that you need to look up to. And there was also just this act of refusal, and the refusal being coupled with the deep, innate feeling that I had—the discomfort that I had—and then being able to put it into words and connecting it to histories or even the archive. That really set off the rest of the work that I'm doing now.

SB:

What about you, Emanuel? How did you get here? Feel free to go back as far as you like.

EA:

Yeah, no, that was wonderful to listen to. I mean—

SB:

Wasn't it just the joy of finding, I suppose, comrades or people who are really vibing off each other and giving each other the courage and motivation to realize themselves? It was beautiful to hear.

SN:

It's the truth. They were there.

EA:

I also think, I mean, just that sensibility of feeling like, you know, we can carve out smaller communities within these dominant spaces and institutions is really, really important. I mean, it was a similar thing for me and, I mean, I went to undergrad in a very technical school outside of Atlanta, and there was just a group of us who were really curious about other ways of doing architecture. Eventually—that small group was about four of us— eventually moved together to New York, and that core group continues to be really the group of people that I test ideas with first even now. I think similarly when I was in grad school, it was clear that there were a couple of professors, who are still mentors of mine, that were charting out territories of exploration that were well-beyond the defined edges of architecture, and that really led me to pursue teaching as a type of practice.

And I went to grad school in the same place that I currently teach. So, there was a moment where I had to escape, and I started teaching at an art school—RISD in Providence, Rhode Island—and that really, really redefined my practice. Just being able to engage with students who are trained as artists, who are now… They're engaging with architecture after they had a long engagement with the arts. Those students really challenged my own approach to teaching and thinking, which eventually really influenced the practice as well.

You know, even now, I'm part of a collective—Black Reconstruction Collective—which is similar, where we just basically trade notes. If we're developing a project, we send a sketch to each other and it becomes this collective that is able to cultivate a form of collective intelligence. And I think that's been really, really important, because we're often reminded that these institutions are not necessarily looking out for us. So we have to find other ways of framing an environment that allows us to be imperfect and that allows us to be able to grow and change and transform. So, I appreciate this idea that it only happens through a series of friendships—a series of friendships that end up shaping a practice, and the practice becomes a way of preserving those friendships.

SB:

This is going to be a great class that we teach one day. Why don't we teach architecture students the value of friendship as a lifelong practice?

EA:

Absolutely.

SN:

I mean, it's really important in friendship, as opposed to rivalry, because specifically the spaces that are then relayed to the starchitects—they're being communicated as soul-practicing agents really divorced from the realities of collaboration, friendship, and codependence. That's just super embedded in architecture, or I think in life-making practices. I still believe that architecture can be a life-sustaining and a life-making practice.

Something that resonated a lot with what Emanuel said on carving out smaller communities and finding your way within institutions, I think for myself, as someone currently employed, most of my days in the week I spent being employed through an institution with great joy—but also always finding myself testing the limits of bringing in people, bringing in ideas, bringing in practices. And it's something that I have thought about more extensively through a project that I have been involved in together with many other people called Collecting Otherwise, which is also specifically about those questions on what and who do we remember in architecture or in our collections. Specifically, there is this subgroup within Collecting Otherwise called the Trojan Horse Cell, and they had an amazing intervention in the institution, and at a certain point, they started calling one of these sub-activations Lumpia on the Threshold of the institution, because they try to get in sources of food nourishment within the galleries. But as you may know, a lot of galleries in museums, they are subject to rules, certain rules, sanitization, and so on. I think it parallels also the sanitization and the rules within an archival complex.

Being on the threshold, we then more literally placed the air fryer on the threshold of the exhibition gallery, and in itself, it really sort of propelled a long-standing thinking—like already thinking for a couple of years about this event, and about what it means to be on the threshold of an institution, of almost being like this agent on the border of or on the fence of bartering knowledge, bringing people in, protecting people, sometimes acting like a blanket, trying to enact a different form of inhabiting the institution. For me, this is really also at the core of what an institution can mean for the public, what it means to have a public institution, and how an institution can employ itself towards collective enlightenment, liberation, all of these things.

SB:

A lot of the practices that you mentioned are kind of fugitive practices, like a Trojan Horse or blanket, as you were mentioning, to smuggle goods in and across, and the fact that that's a practice that is not only embedded within the institution, but funded by the institution. And Emanuel, you mentioned the Black Reconstruction Collective. Perhaps you could sketch out how that came about and why that came about.

EA:

Some institutions invite you to do a show, and the moment you start developing that show, it becomes clear that they don't actually want you to do that work. They want you to allow them to check certain boxes and be able to say, "Hey, we did this show on Black architecture," but when it comes to really subjecting architectural value systems to Black studies, that's absolutely not what they want to do. So for us, I mean, the 10 of us were invited, and it was a brilliant curatorial project by Mabel Wilson and Sean Anderson. And they knew that we were going to be facing these constraints when we encounter the MoMA as an institution. So, they framed it almost as a kind of seminar. So we were doing a series of workshops presenting work to each other, and there would be these really amazing people coming and seeing our work and commenting on our work, but at some point, you pass that threshold of this space of refuge that's been carved out for you by the curators, and you begin to understand the weight of the institution.

And at that point, it was clear that the institution wanted to deal with individuals. So there's this obsession with individuation and Western liberal political orientation claims that that's how you gain liberation. But it became clear that when they were speaking to us as individuals, they were actually trying to compromise the work. So we basically started our own side conversation—the 10 of us—and said, "Okay. From now on, we're only going to speak to them as a collective." So the collective was formed in real-time as we encountered the institution and the constraints that it was imposing on our creativity and the type of ideas that we wanted to explore, et cetera, but that experience also made us understand that it has to go beyond the 10 of us. So, the collective became an institution that just offers intellectual and funding support for other folks who are doing similar work in the realm of spatial liberation.

So yeah, we formed a nonprofit, and now we have, you know… been able to raise a decent amount of money to support folks who are doing incredible work, but we're also really trying to make sure that we cultivate this environment to have these discussions and retreats and just allow people to present work that is in progress. So, for the most part, that's what the Black Reconstruction Collective has been.

But going back to what you guys were saying earlier around these borders and classifications that are established between even something like architecture versus life—I mean, for me, it's like some of it goes back to cultural sensibilities, as well. Quite simply, growing up in Ethiopia, these borders just did not exist. So, to a certain extent, we're also trying to live the types of lives that we want to live and also try to cultivate practices that feel natural to us. And sometimes you're dealing with this Cartesian logic that is trying to really enclose every aspect of your life, and even though it can be rendered or narrated as a subversive practice, to a certain extent, we're just trying to go back home. I think that search for home and for something that actually feels like it's nourishing feels so foreign to these institutions.

Simultaneously, when we're doing this work of forming communities and establishing solidarities across geographies, then it makes those institutions look kind of crazy and really, really static and boring. So when we keep doing this work, eventually, of course, they will be interested in whatever we're doing, and then we get to determine our engagement with them on our own terms. But recently, I've been trying to think, "Okay. Maybe this is just the basic thing." It's not this monumental subversive act, but it's me trying to understand a feeling I had when I was in certain environments back home growing up, and how that feeling comes with me to New York. It's a very simple thing, but it's very difficult to achieve sometimes, when you're dealing with these rubrics and value systems that are imposed on your work.

SN:

Yeah, no, definitely. I mean, picking up on the institutional part of the ability or the inability to practice for freedom or rehearse for freedom, I still think that the institution is still, luckily, not a monolith in the sense that working in an institution, you see how all of these value systems in part are paralleled or clash with each other. But you see these pockets forming—like pockets of intelligence, pockets of resistance, various ways of helping each other. In these spaces of mutual aid, there is so much change to be realized, and that's something that I find really beautiful. Like doing these projects, you can rally so much more support than initially thinking when you are reading either a “canon” or a list of books to tick off, these types of rubrics that are enshrined in whatever format that you may find them.

In terms of getting back to home or the home place or practices of homemaking, that's something that I always have been curious about. I grew up in the Netherlands. My father is from Iran, my mom is from Somalia. So you already have a diasporic element in there.

EA:

I knew you were a Somalian. Horn of Africa.

SN:

Yeah, the Horn of Africa and congregating, again, like speaking from one country to the other from the Horn. But this feeling of return always has been quite abstract to me, and it has been vocalized through my parents to me without me knowing, in a sense, what that meant. Growing up here and in the past few years, I've been doing so much more traveling. Luckily, I've been privileged, and finding again these spaces that mirror almost what I think I know or that which my parents have showed me when I was growing up or even the few times that I went back to Iran and saw my family there. You learn the facts on the ground and you learn what it means to have taken the decision to move to Europe, like passing all these borders, the militancy of these borders, and still the ongoing longing for return.

So I'm trying to get a grip on that abstract feeling through some other research projects, but also through my art practice and digging up almost the remains of the artifacts that my parents have left me behind and seeing what I can understand still from them. Sometimes I think, "What if all the diaspora, what if we came together almost formed?" I mean, I'm against the nation-state, but sometimes it feels like, "Oh, I have so much in common with other people who have found their home elsewhere."

EA:

Yeah, that's so beautifully put.

SB:

For those listening in the podcast, we're all nodding vigorously at each other, all of us having been separated from various places of origin at one point or another in our heritage.

EA:

What I was trying to say about the search for home is, in some ways, dealing with the impossibility of the return, and that's something I'm definitely dealing with because, obviously, there are various forces beyond my control that led to my migration to the US or my parents' decision to send me to the US for education. Similarly, there are a series of events unfolding in Ethiopia that also continue to remind me that there is a reason why I am here. And I think there's something about refusing the static nature of any of these places or their attempts to pretend to be static. And I feel like I'm still trying to figure it out, but sometimes home feels like Atlanta, Georgia, where I went to for high school. Sometimes home feels like New York, and sometimes it feels like Addis. There's also, for the past few years, I've been spending a lot of time in Dar es Salaam, and that’s really, really starting to feel like home as well. So I think we're looking for fragments and hints in all of these places that feel familiar and that feel welcoming. I don't want to sound nostalgic or pretend as if somehow returning to Ethiopia will lead to some form of liberation, right?

SN:

No, no, exactly. I think, again, we have to rehearse freedom where we are, and we can also find freedom through these friendships and through the act of making do, or the various acts of making do.

SB:

I mean, I'm getting quite emotional listening to you both. I think there is that impossibility of return. I mean, speaking specifically about those who are held in some way by their heritage, either by experience or by inheritance to a place but also a time. It's like that cliched saying that you can't step in the same river twice. The Calcutta that I grew up in has been renamed to a Kolkata that I didn't grow up in. The political situation that I grew up in is not the one that endures, and there is no return, and yet there's huge kinship that I feel both with that place and people from it, but also with all of those like you.

Perhaps that's making do in terms of the impossible return, but I think it's also massive. It's so much bigger. It's much less fragile than a memory, than nostalgia. It's much more generative. I mean, I've been noticing this in architecture culture, slowly making its presence felt. The Venice Biennale last year was a moment of celebration, and I think that kind of common grounding for all of us who've been on the threshold. But yeah, I don't know whether quite to feel optimistic about it, but listening to you talk about this experience that you're trying to locate in your various practices of teaching, making architecture an art, is really inspiring. Please keep going.

SN:

Perhaps to throw in another word, or even taken from the Black Reconstruction Collective, like the act of reconstructing and the act of imagining otherwise. Perhaps that's something that we could get into. Is it either reconstructing this memory or embodied knowing of living together and making otherwise? It's also deconstructing, I think, many systems. It is fighting against unwanted boundaries, borders, enclosures. Just thinking about that.

EA:

Yeah, and really genuinely believing that another type of world is possible. Some of what unites diaspora communities, I think in cities, like… Whether it's Rotterdam or London or New York… is precisely how folks are dealing with the loss and how they're imagining another type of world. I don't know; I think that, to me, is so much more productive than these ideas and origin stories that some folks are really committed to, which makes it difficult to be self-critical, and it makes it very difficult to understand how we're implicated in some of the violence that is out there. I think the self-righteousness sometimes is also counterproductive,because these algorithms encourage us to be self-righteous, encourage us to be pure. Whereas when we're encountering some of these challenges in real-time, we begin to understand our own aspects of our personalities that might seem relatively conservative or that are unable to change.

So to take a tangent a little bit, I've been working on this book called Where is Africa for the past seven years, and part of the ambition with the book was me and a friend came together and said, "Okay. Who are the people that we want to have long-term conversations with?" It just became a book about these long-term conversations. None of those questions led to clear answers, but at least we're able to identify a certain ambience of dissatisfaction—but also a certain drive to keep imagining other types of worlds. To me, that's at the core of practice, period. I hope I can maintain that energy somehow, because the moment I feel really comfortable in any of these environments, or comfortable with any of these origin stories, then I'm not doing the work anymore.

SN:

It's also about debunking the myth of exceptionalism, and that's specifically tying back to the myth of the starchitect or even tying back to the nationalist myths of country-focused retrospectives, for instance, in exhibitions. So we're thinking a lot about that, actually, at the Nieuwe Instituut. So it may be… It’s something that I'm thinking about now a lot, so it may be a tangent of mine, but in making an exhibition that's currently on show—it's called Designing the Netherlands—something that I thought about a lot was, what does it mean to design “the Netherlands?” As an entity in itself, it's already very exclusionary because the Netherlands used to also mean all the colonies, not too long ago, in which Dutch design and Dutch architectural design and urban planning has been implicated in carving out space, making that space between—quotations—“productive,” getting the earnings and everything—back to quotations—"the motherland,” all of these truths that I think are also part of where we find ourselves now in the midst of many unfolding crises, be it social, be it ecological, right?

Another part of debunking that myth is also the agency or the work in being done to make visible or make legible, which is sometimes in itself also a practice. That's very discomforting, this thing where you want to shed truth and want to shed light on certain lives or paths people have taken and coming across gaps as well, right? Things that may not have been of interest for previous generations working with architectural culture or collecting these narratives. And then still, how do you think about these gaps as something that are in itself not, again, a box to be ticked off, but a prompt that you have to be held accountable for, over and over, as long as you remain committed to these histories? I find that very important. It's not something that we close off and then move on.

SB:

Can you give us an example, Setareh?

SN:

Yeah. For instance, just the immense work that we are currently doing and still need to be doing and collecting diverse voices for the collection that we hold—acquisitioning actively voices of women architects, architects from the diaspora, for instance, from Suriname, the islands like Curaçao or Indonesia—and making sure that their histories are seen in the light of Dutch architectural practice if it's in that exchange. And something that is also, for me, very interesting is how to debunk the myth of not only Dutch design, but also to add multiples or to add more than one lens to the lens of modernism or to the lens of the vernacular, to open that category up again because often when you acquire, for instance, a new voice to the collection, it holds the danger to be boxed in again and not to be seen as a brilliant practice of its own.

SB:

I was also going to bring up a couple of other words that I scribbled down for this conversation. Again, around the time when I encountered you both, one of the words that was flying around in 2020 was “reparations.” I think “reparations” and “legacy” are words that I've written down in relation to this conversation about archives and who holds them and who goes in them and whatnot. So, I don't know, I mean, certainly as I said at that period of time, in 2020, the word “reparations” had quite a lot of charge, and we were talking about it within academia, which was also provocative and discomfiting in some ways. Is that still a concept that holds water for you, Emanuel?

EA:

Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I would say there are some brilliant folks thinking about reparations in various ways. Even right now, my colleague Paulo Tavares is teaching a studio on reparations here at GSAPP, and there's been a few journals focusing on reparations that came out over the past few years that have really made major interventions on architectural discourse, I would say.

I also think—for me, at least—with the timing of the MoMA show and the fact that it was slated to open in 2020 and eventually opened in '21, and the conversations around the show and how discourse was framed in fall of 2020 versus, let's say, fall of 2023... It just shows that I think we need to be careful about developing projects that are long-lasting and they don't become projects that basically have a sharp impact for a very short period of time, and then evaporate. If you look at architecture lecture series, for example, that all the major universities—let's say the Ivy Leagues in the US—if you trace who was lecturing in fall of 2020—I would even push it to spring of '21—versus who is lecturing in 2023, it just shows you that there was a brief window where they wanted to engage with certain questions around coloniality, around anti-Blackness, and then now they're like, "Alright. We addressed that. We're back. We're back to talking about things we were talking about in 2013."

This reflex is so fascinating to me because—and again, I'm being very general because I think Setareh is being more generous than I am, and the fact that, obviously, these institutions are complex and they have folks within them that are destabilizing them and unsettling them—but by and large, a lot of these institutions just assumed 2020 was a brief window, and that whole racial reckoning that was happening in summer of 2020, fall of 2020, was something that had to happen for a very short period of time, so everyone can get back to whatever they were doing before that. And that's deeply frustrating, but also unsurprising. I think what do we do with that is kind of where we are now, especially at this moment where it's clearly a moment of retrenchment, where any gains that might've been made 2020, 2021, are now kind of being erased or moved to the side.

So I think we just need to make sure that we are constantly inventing new vocabularies. And “reparations” was extremely productive, and I think it's still productive today, but we need like a hundred other words that have similar impact when it comes to really transforming the world, because it's clear that the increasing forms of fascism that we see in Europe, here in America, all over the African continent, Asia—they are constantly updating their language. They're constantly updating their strategies. So there is no reason that we should assume we can keep using the same methods every year. So, I think the iterative aspect of it is something that we need to be very serious about and really practice moving forward. So that's generally my feeling around reparations.

SB:

Well, I'm glad to hear it. I mean, certainly in the UK, it's not a term that gets... Because can you imagine what reparations would mean for the UK? It's sort of a quite scary word, I think, certainly for institutions or those with authority who may feel that perhaps those things come into question. Setareh, I don't know how much currency the word “reparations” had in the Netherlands or in your community.

SN:

Yeah, of course. It has been spoken about quite widely as well, in that particular timeframe of Black Lives Matter. I would say that I find myself, aside from “reparations,” I use a lot the word “remittance.” And what I found productive in the word “remittance” is that it bases itself on a continuous circulation of ideas, economies, opens up doors—I think more than that—but also just keeps on holding this accountability high on the priority list. There's always more to remit, and there's always more to circulate. Something that I believe, and this is also from conversations that I had, especially that period coincided with the first year of starting up Collecting Otherwise—so it was a period in which the urgency for this project within an institution was just as clear as day. It was interesting that the conversation was also about how do you define remittance, and I immediately said, "Remittance does not mean that you will lose things. It is that there is an exchange of things, based on what both ends or all ends value, and what keeps grounds for a lasting relationship."

I think that's the thing, as well. We need to always be in touch with each other while we are doing the work. And the work is often also a tedious work. Like Audre Lorde said, "What does it mean to do the work?" I think keeping in touch with each other also means that you do not run the risk to becoming the oppressor yourself. You always maintain a horizontality. You always maintain a connection.

EA:

Yeah, absolutely. Similarly, I've been just… Even this course I've been teaching on restitution, it's not really about just returning these looted objects. It's actually about acknowledging the asymmetry that continues to frame the relationships, at least between Europe and Africa, and how we have to move beyond the nation-state to imagine other ways of relating to one another.

So, we can just keep adding terms to this, but it's really about finding ways to keep challenging these hegemonic definitions of the human, even, and trying to understand other ways of relating with technology, other ways of relating with movement and migration and identity, but always really being aware of the power that is embedded in these histories that have shaped the world. For example, there's been a lot of conversation around “the commons,” like commoning in architecture. I'm all for it, I love it, but we can't get to the commons without really dealing with some of these notions, whether it's remittance or restitution or reparations. We can't just go there because the ground has been shaped. So we have to deal with the ground first before we start commoning it. I think that's really important, and it's difficult work, and it's not sexy. It's much sexier to say, "Hey, this is about the commons, forget it.” But I just think there are no shortcuts, and this is difficult long-term work, and a lot of it is working on ourselves first.

SN:

Yeah, especially when the commons has been taken away from us first. It has been appropriated, it has been extracted, it has been put to use for capitalist devices, and then to reclaim back the commons is to undo capitalism and imperialism.

EA:

Amen.

SN:

Yeah. Something that I'm still thinking about—also through this conversation—is, and we haven't touched upon that yet, not explicitly, is the question of the center and the question of the margins, right? Emanuel, when you were saying earlier about asymmetries, that we first have to contend with what is on the ground, I think it's also about dealing with what is still seen as center margins. But then still, and this is a question, I think, what could be a more useful way for us to think?

SB:

That's actually a great point. It reminds me of a phrase that I've scooped out of your bio, Emanuel, but just because it grabbed me, and I'm sure I'm using it out of context, but I'm going to refer to it. You mentioned something like the “immeasurability of Black spatial practices.” I suppose, Setareh, you're talking about metrics and the problematics of various systems of measurement. So perhaps this is a place where we can talk a bit.

EA:

Yeah, basically, I'll say that is, in some ways, the big project where just really thinking about measuring and what measuring means to architecture, which we've been told from the beginning, that is foundational. But yet there isn't at least enough accounting, in my opinion, of why we measure. Are we always measuring to own? Are we always measuring to compare the value of things? So, if we put that aside and say, maybe there are practices that the tools of architecture and the tools of some of the dominant spatial practices that we associate with architecture are unable to contain or measure, then hopefully that moves us in a direction that is a bit more self-conscious and a bit more critical.

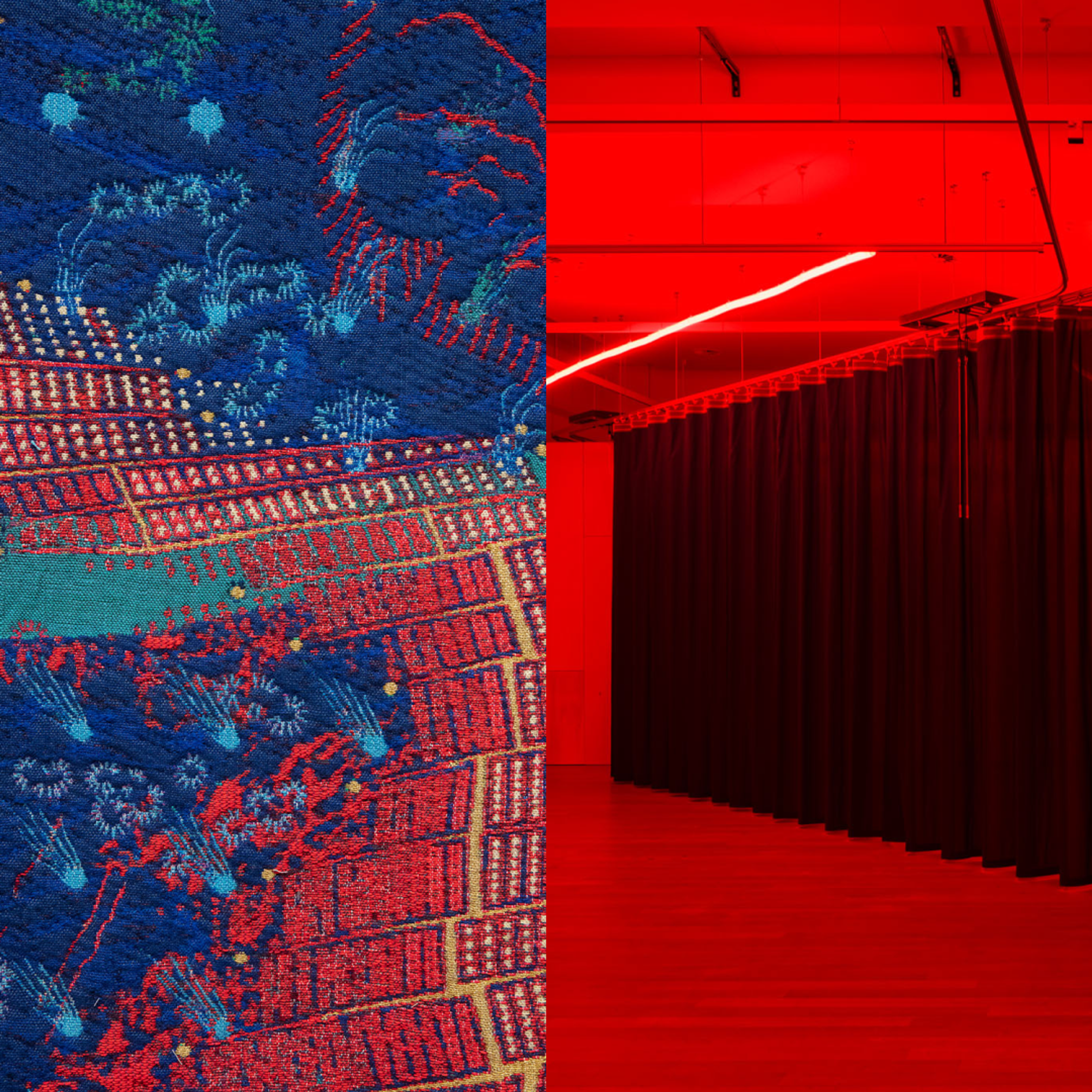

This notion of immeasurability also obviously addresses other ideas of fugitivity, and even in what you were saying, Setareh, about the center and the margin, that assumes a certain fixity in the way that our histories have been narrated. I think this notion of immeasurability, at least, begins to say there is no clear rubric in understanding what the center is and what the margin is, but yet we're finding ways to move through these spaces. So it's been really generative and it's also kind of, at least for our practice, been a way to keep us from reverting back to certain conventions of imaging that we associate with spatial practice. That's precisely why we kind of have started going more into the realm of tapestries and just really dealing with resolution and legibility as a way to think about space.

SN:

Yeah. And that was also a great clarification, Shumi. Thank you so much because, exactly, I wanted to get into that and the alternatives that we have and immeasurability. Something that I try to do within my design practice is to think of what kind of spaces do we want to carve out with our Black bodies, with our queer bodies, with our female bodies or non-heteronormative bodies, and what does it mean if these spaces are to be designed for institutions or within institutions? Is the one already canceling out the other?

Specifically, I've been then grappling with the question of measurement or measurement as related to movement, measurement as related to the ability to appropriate space. And that brings us back again to, I would say, very traditional architectural tools or sizes and subverting these sizes the way that they are implemented as elements within a space, subverting Cartesian space in that as well because a gallery space is often a rectangle—thinking about these types of spatial constraints and how to undo them through experiment because an institution, especially a museum, warrants still for these types of experiments if they are done under the umbrella of exhibition.

SB:

For me, the other thing that—or maybe, I might even say the best thing about immeasurability, aside of the fugitive and liberating potentials of that—is the generosity, the fullness of suggesting that something is immeasurable. Even the drops of water in the ocean could be measured, feasibly, but the generosity of the suggestion that there's a world that is boundless, bound only by your own participation and imagination of liberatory practice, that's the most optimistic reading and the most joyful reading. When I read that phrase, I kind of disconnected it from the other words around it. But yes, immeasurability of Black spatial practice is definitely a long-term goal worth having, Emanuel. Thank you for giving me that phrase.

At the same time, I was really taken by your plea, Emanuel, earlier, where we're just trying to live and we're just trying to go home. We're talking about fundamental freedoms and social imaginaries and so on, but at the same time, this comes down to quite mundane day-to-day activities of… How do you balance the fact that what we're thinking about seems on the one hand so ambitious, and on the other hand, you're trying to play that out in the banality of life?

EA:

I'll give it a go. One thing I've been trying to practice, even just with my students, is just being generous and acknowledging their time. In architecture school, there's always this demand for production and demand that they don't sleep or eat, but they produce. What I've been trying to do, at least just in the framing of the studio and the way we engage with things, is to just give things time and just say, "You guys just have to read one essay this week and work through that essay, process it, meditate on it, and through our discussion we'll be able to figure out what you want to do with it."

I feel like we're all dealing with the barrage of emails and demands and whatever kind of work we're trying to do. I can speak for myself. I feel somewhat overwhelmed, and I feel like part of my job—in academia at least—is to try to make sure that my students that I'm working with and that I'm thinking with feel a little bit less overwhelmed, and they just have space to think through these really difficult questions. I think that automatically sets the tone from the beginning, and at least some of the anxiety goes away, and we begin to have real conversations when they have time to just process the things that we're grappling with. To a certain extent, that's kind of what I'm trying to figure out in my own practice, too, day-to-day—just being like, "Okay, I'm not going to get to those 30 emails. I'm probably not going to meet the deadline for that essay, but I have to find a way to kind of go to sleep feeling okay about the fact that I'm not meeting these demands."

It's also the barrage of information and the kind of emotion that we're processing through social media. And I think these real encounters—whether it's through practice or through teaching— hopefully should be spaces where we say, "Okay. Can we turn those things off for a little bit and just give ourselves time to think and to orient the work that we're doing?" I know it's not necessarily addressing exactly what you were asking, Shumi, but I think it's just really subtle and feels like it's necessary. At least to me, it feels necessary at this moment.

SB:

No, I think it's really generous of you, Emanuel, to share all of that highly relatable struggle, but it is how it's done, in a sense. To imagine hyperproductivity and unethical labor practices while trying to perform liberatory work would be a nonsense. So, I'm really glad that you were so candid about it because I think it bears repeating.

We've been talking about the fluid beings that we are. Maybe some people have developed modes of operating in compartmentalized ways, but part of liberatory practice is realizing that perhaps we don't have to, and perhaps all of us can be welcome and we don't have to censor those parts of us that are not traditionally seen in certain places, in certain ways. So yeah, maybe, Setareh, you can talk a little bit more about some of that bleed and how it helps you to not only mitigate the weight of the struggles, but actually operate through them in lots of different ways.

EA:

I want to add one question to that. I mean, I think a lot of the discussion today has been just about the politics embedded in our work, but I want to hear about your relationship to aesthetics because there's a clear aesthetic orientation to the work.

SN:

Yeah, no, definitely. Okay. So, first about the overlapping or the bleed of different practices into each other—I think it also warrants for something else that I like to call for, which is opacity. I like to explain certain things to where I see them fit and where I see them belong. Not everything is immediately to be left for the public. There are certain things that I'm doing that relate deeply to that. I also respect that a lot with the people who I encounter, specifically if I'm the nosy one trying to dig up their histories in relation to the archive.

What I find very necessary is that architecture—or sort of providing aesthetic expressions to the space that we inhabit and encounter—is not only seen as mapped out built structures, but they can also be vocabularies. They can also be sonic experiences, can also be the mappings and the structures that we build through organizing work, and that's something that all of the things that I do share in terms of the structures that I build or design for. And I do that, always, in collectivity. I like doing that. I like also inviting more people into a specific assignment, even though that's sometimes not appreciated at the start of me trying to fulfill the brief. I think it's me trying to give, first of all, expression to the desire for change within the brief, which is always apparent, and sometimes it's communicated through hesitation, and I'm trying to make that explicit. And I'm also trying to make explicit the usage of different form and different color that's specifically counter to the space that it tries to inhabit at that certain point, but moves with the content that I'm trying to express or try to communicate through the design.

That's specifically, I think, one of the largest tasks if you are assigned to design an exhibition for artists or for artwork—to create a certain proximity to the artwork, to create an interrelation, also understand the needs of the artists, and at the same time deliver something that you feel adds to the public's experience of that specific institution. Often, it means, in my opinion, decolonizing as you go. With the intervention, you are decolonizing. I really like to infuse beauty in the spaces because I think that's something that we deserve.

SB:

Absolutely. I'm feeling like I could listen to you guys forever, and every time I think, "Okay, that's a great place to wrap," something else pops up that's just beautiful, but I think we're coming to time.

EA:

Yeah, it was just great to have this conversation, and hopefully we'll be able to continue.

SN:

Yeah, in Rotterdam.

EA:

Yes, in Rotterdam, London, and New York.

SB:

All right. We hope you enjoyed that beautiful exchange between architect and artist, Emanuel Admassu and researcher, curator, and architect Setareh Noorani. Of course, you can find more information on both speakers and the rest of the series in the show notes, on the re:arc institute website, and on the digital platform KoozArch. All episodes of the podcast, all equally insightful, can be found through Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you listen to yours. I'm Shumi Bose. You've been listening to Between Us, the second season of Architectures of Planetary Wellbeing Podcast. Thank you so much for joining us and stay hopeful, happy, soft, and strong.